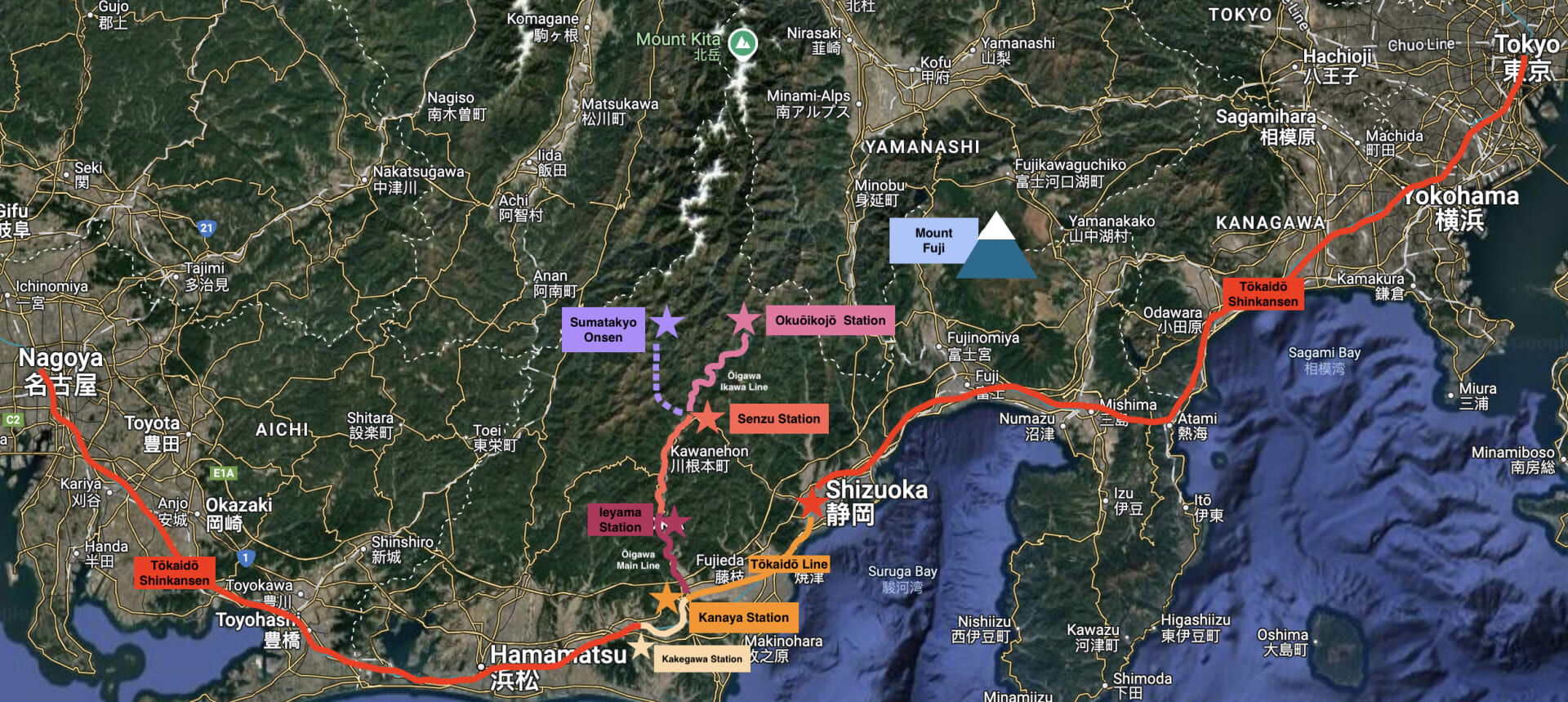

After spending the day exploring some of Tokyo’s many great train-related attractions, my friends arrived in Japan and we kicked off the first leg of our railway adventure! Our first journey was an ambitious one. We travelled for over six hours on three trains, a bus, and then yet another train, all to reach one of the most remote train stations in the world: Okuōikojō Station. Our itinerary was tight, with usually just one viable connection at each transfer point. Missing a single train or bus would have stranded us in an isolated area with no easy way forward. Along the way, the route offered an incredible bonus: the chance to view Mount Fuji from the window of our Shinkansen.

From Tokyo to Kanaya: Riding the Rails Beneath Mount Fuji

Our journey began early in the morning at Tokyo Station, where we boarded our first train, the Tōkaidō Shinkansen, bound for Shizuoka Station.

The Tōkaidō Shinkansen runs south of Mount Fuji, offering travellers a chance to view the iconic mountain from the train. This was the only train we had booked in advance, as we wanted to ensure we secured seats on the Mount Fuji side of the train. Since we were travelling toward Nagoya and Osaka, this meant sitting on the right-hand side. For the rest of our 10 day journey, we simply purchased tickets at each station as we went.

On this leg of the journey, I enjoyed a train-themed ekiben for breakfast. Ekiben are compartmentalised bento boxes designed for rail journeys, typically featuring a variety of small dishes. I purchased mine from one of the ekiben stores inside Tokyo Station, just before we boarded our Shinkansen. Ekiben come in all shapes and sizes, often themed to reflect regional specialties from the station where they are sold.1 Some even include clever features like pull-strings that heat the food inside.2 My meal came in a box shaped like Doctor Yellow: Japan’s high-speed diagnostic train used to monitor track conditions and overhead wires. Spotting the real Doctor Yellow is apparently considered quite lucky in Japan.

It wasn’t long after departing Tokyo that the imposing Mount Fuji began to emerge in the distance. Unfortunately, dense cloud cover shrouded the summit, obscuring the view and making a good photo impossible. En route we also passed Odawara, which my guidebook informed me was once an important castle town.3

Shortly after, we passed through Shin-Fuji, which my guidebook rather bluntly describes as notable for its ‘hideous smoke stacks’.4 Shin-Fuji Station is situated in a distinctly industrial area, with some of the smoke stacks visible in my photos of the station below.

After our 80 minute journey on the Shinkansen, we alighted at Shizuoka Station, where we had a 20 minute wait for our next train. The city of Shizuoka has a ‘friendship city’ relationship with the city of Huế in Vietnam. You can read about my train trip to Huế in a previous blog post.

While we waited for our second train of the day, I warmed up with my favourite drink I’d discovered in Japan: caramel tea, dispensed piping hot from a vending machine. In addition to offering hot beverages, I found that the drinks in Japan’s many vending machines were also very affordable.

From Shizuoka Station, we transferred to the Tōkaidō Main Line which largely parallels the Tōkaidō Shinkansen.

We travelled for just over 30 minutes to Kanaya Station, where we then made a quick seven minute connection to the Ōigawa Railway.

Introduction to the Ōigawa Railway

The Ōigawa Railway follows the course of the Ōi River towards the southern Japanese Alps in Japan’s Shizuoka Prefecture. The railway’s Main Line stretches between Kanaya Station and Ikawa Station. First opened in 1926, the railway played a vital role in transporting timber, freight, and tea through the mountainous regions along the Ōi River.5 However, usage of the railway declined sharply following the completion of local dams and the expansion of Japan’s national highway network. In 1976, the privately owned Ōigawa Railway Company came forward with a new vision for the nearly obsolete railway: turning it into a tourist attraction!6 Today, steam trains traverse the scenic Ōi River valley, winding through Japan’s tea-growing heartland. Although tea fields are actually quite rare in Japan, many can be found throughout the Shizuoka Prefecture.7

Ōi River and Japan’s Maglev Project

Interestingly, it is the Ōi River and Shizuoka’s tea plantations that have delayed Japan’s maglev project for over a decade. Japan’s Chūō Shinkansen—a maglev line currently under construction between Tokyo and Nagoya (and eventually Osaka)—was once promised to be the future of high-speed rail. Using superconducting magnetic levitation technology, maglev trains hover 10 centimetres above the track, guided and stabilised by powerful electromagnets. Testing has shown that Japan’s maglev trains would be able to travel at speeds exceeding 600 km/h—nearly twice as fast as the current Shinkansen bullet trains. Their levitating design doesn’t just make them fast, it also makes them safer. Derailments, a serious concern for traditional rail, particularly in earthquake-prone Japan, are virtually eliminated thanks to the U-shaped guideway that automatically re-centres a maglev train if it veers off course.8

The Central Japan Railway Company (JR Central) initially aimed to launch the maglev line between Tokyo and Nagoya by 2027. However, a significant roadblock to Japan’s next-generation rail system has been the Ōi River and staunch opposition from Shizuoka Prefecture. At the centre of the dispute lies an environmental concern: Shizuoka officials have refused to grant construction permits for the short section of the railway that crosses the prefecture, citing fears that tunnel excavation could reduce the Ōi River’s water levels. The river is a crucial source of irrigation for the region’s tea farms. Shizuoka accounts for over 36% of Japan’s total tea production and local farmers fear that disrupting underground water flows could devastate their livelihoods.9

For over a decade, Shizuoka’s Governor Kawakatsu was a vocal opponent of the maglev project, insisting that the tunnel posed an unacceptable risk to the river and, by extension, the local agricultural economy. Yet, some critics believe the environmental concerns may have be a smokescreen. Shizuoka is the only prefecture along the maglev route without a planned station, meaning it stands to gain little from the project’s economic benefits. It is thought that Shizuoka’s prolonged resistance may actually have been an attempt to pressure JR Central into building a station in the prefecture.10

Things came to a dramatic head in April 2024. Governor Kawakatsu sparked outrage after publicly claiming that his staff were “smarter than people who sell vegetables or raise cows.” In a prefecture whose economy depends heavily on agriculture, including the very tea farmers he claimed to defend, this elitist remark was political suicide and the backlash was swift. Within 24 hours, Kawakatsu was forced to resign.11 With new leadership now in place, JR Central has finally been granted approval to begin work on the proposed tunnel route through Shizuoka. However, years of delay have cost Japan precious time. China has now surged ahead, boasting the world’s largest high-speed rail network and fast advancing in maglev technology.12

Ōigawa Railway Main Line (Kanaya—Ieyama)

Our 45 minute journey on the Ōigawa Main Line from Kanaya Station took us past countless tea fields and offered a scenic glimpse into the region’s rich agricultural landscape.

According to my guidebook, the conductor was supposed to pass through the train playing a harmonica or singing over the loudspeaker but, disappointingly, that never occurred.13 We alighted at Ieyama Station, where we had a 20 minute wait for our next mode of transport. While waiting, we spotted an interesting train on the siding. The Ōigawa Railway has five locomotives modelled after characters from the Thomas & Friends children’s television series. During the winter months, however, these character trains go into hibernation. While their presence would no doubt be a delight for children, I was glad to have visited during the off-season, when the regular trains were running.

The sign in the first image, adjacent to the railway tracks, reads ‘Protect the Ōi River, which conveys the blessings of the Alps and connect it to the sea and the future (Research Council for Protecting the Pure Waters of the Ōi River)’.

Previously, it was possible to travel on the Ōigawa Main Line all the way to Senzu Station. However, in 2022, the railway suffered significant damage during a tropical storm. Rail services between Kawane-Onsen Sasamado Station (located just north of Ieyama Station) and Senzu Station have been suspended ever since. Passengers intending to travel beyond Ieyama Station must now transfer to the Kawanehon Town’s community buses at Ieyama Station, which provide a connection to Senzu Station.

We therefore boarded the bus at Ieyama Station for the 40 minute journey to Senzu. In many of the photos taken from the bus, you can see the tracks of the currently disused railway line between Kawane-Onsen Sasamado Station and Senzu Station.

After arriving at Senzu Station in the quiet town of Kawanehon, we found ourselves with just over an hour before our connecting train.

In the station building we came across a model of the Wengernalp Railway which connects the villages of Lauterbrunnen and Grindelwald in Switzerland. The Wengernalp Railway is the world’s longest continuous rack and pinion railway. My 2014 journey on this railway is detailed in an earlier blog post.

While waiting for our next train, we walked around the town, where I enjoyed a warm plate of Katsu Curry for lunch.

We also visited a small steam locomotive museum located next to Senzu Station.

Before continuing our journey, we stored our luggage in coin lockers at Senzu Station, allowing us to travel bag-free for the rest of our trip deeper into the mountains.

Ōigawa Railway Ikawa Line (Senzu—Okuōikojō)

Before long, we were climbing aboard our next train! The Ōigawa Railway Ikawa Line runs from Senzu Station to the terminus stop of Ikawa Station. However, we planned to alight a little over an hour into the journey at Okuōikojō Station.

This segment of the route is notable for containing Japan’s only Abt rack railway. Between Abt Ichishiro Station and Nagashima Dam Station, the gradient is extremely steep and requires an Abt System electric locomotive to be attached to the rear of the train. When plans to turn the Ōigawa Railway into a tourist operation were first conceived, the company took inspiration from Switzerland’s Brienz Rothorn Railway, which uses the Abt system devised by Swiss mountain railway engineer Carl Roman Abt. The Brienz Rothorn Railway travels from the turquoise waters of Lake Brienz up to the Rothorn Kulm summit station. While I have not travelled on this particular railway, you can read about my train journey along Lake Brienz here. In 1977, the Ōigawa Railway and Brienz Rothorn Bahn signed a sister railway agreement.14

We alighted at Abt Ichishiro Station to watch the coupling operation of the Abt System locomotive and the toothed rack rails.

Once we were back on board, the train ascended the very steep incline to Nagashima Dam.

Okuōikojō Station

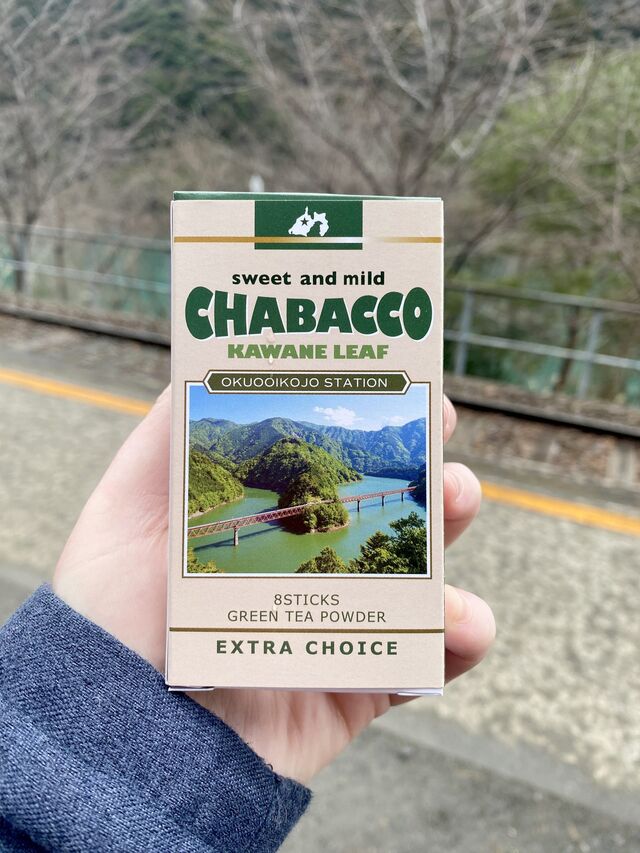

Just over an hour into the journey, the emerald waters of Sesso Lake came into view as the train made its way along the Okuoi Rainbow Bridge which stretches 474 meters across the lake. We had finally reached Okuōikojō Station!

Opened in 1990, Okuōikojō Station is used only by tourists.15 The station is perched in the middle of the Okuoi Rainbow Bridge, on a peninsula overhanging the emerald lake, deep in the mountains of the Shizuoka Prefecture. I had wanted to visit this train station for many years, ever since I first read about it on a list of the world’s most remote stations.

The railway to Okuōikojō was initially constructed in 1935 to transport workers and materials for the construction of the dam, but due to its spectacular location, it was decided that a train station should be added to this section of the line. The station was eventually opened in 1990, when the Ikawa Line was re-routed to avoid the rising waters of the lake that was caused by the Nagashima Dam.

We had 1 hour and 20 minutes before our return train to Senzu. There is a cafe located next to the station, however, it is only open on weekends and closed all together during the winter. There is also an observation deck which can be accessed by walking to the end of the Okuoi Rainbow Bridge and then climbing a steep set of stairs. It took about 15 minutes to reach the viewpoint, where we enjoyed a beautiful view of Sesso Lake.

We were very lucky with our timing and were able to watch another train pulling into Okuōikojō Station from the viewpoint.

After an unforgettable visit to what is perhaps the world’s most beautifully situated train station—and certainly my favourite station I have ever visited—we boarded our return train on the Ōigawa Railway to Senzu Station.

Sumata Gorge Region/Sumatakyo Onsen

After returning to Senzu Station and collecting our luggage, we boarded a 40 minute bus bound for the Sumata Gorge region and Sumatakyo Onsen, which is famous for its hot springs. When planning this trip, it was somewhat unclear if this bus would actually be operating as we had found conflicting winter timetables on the internet. However, before our trip, I contacted the Ōigawa Railway Company and a helpful employee assured me that the bus would be running. Luckily the bus showed up and we made our way to Sumatakyo Onsen and checked into our accomodation at the Suikoen Ryokan.

This was a great deal, with a traditional Japanese dinner and breakfast included, all for under $100AUD per night.

The following morning, we enjoyed a lovely breakfast, before setting out to explore the town.

We also walked to the Yume no Tsuribashi Suspension Bridge (also known as the ‘Bridge of Dreams’): a famous rickety bridge suspended between two mountain ridges, over the crystal blue waters of the Oma and Sumata Rivers.

After our morning of exploration, we had a rather curious lunch in the town centre. About 20 minutes into our visit to a small soba restaurant, the elderly lady who worked there suddenly insisted that we wear masks, though it wasn’t entirely clear why or how, considering we were just about to start eating. The whole thing was made all the more confusing by the fact there were three of us and she only presented us with two masks.

Journey to Nagoya

In the afternoon, we boarded the Sumatakyo Bus Line back to Senzu Station, before riding the Kawane-Honcho Town Community Bus to Ieyama Station, and the Ōigawa Railway Main Line to Kanaya Station. During the journey between Ieyama and Kanaya, my friend Jif casually wondered aloud whether Mount Fuji might be visible from this location. I turned around to glance out the window behind me and there it stood, crystal clear and towering over the villages below. This was a great sight after the disappointment of the mountain being obscured behind clouds the previous day. After alighting at Kanaya Station, there were also great views of Mount Fuji from the platform.

From Kanaya Station, we continued our journey by travelling on the Tōkaidō Main Line to Kakegawa Station.

We then boarded the Tōkaidō Shinkansen bound for Nagoya. We arrived in Japan’s fourth-largest city approximately four hours after having left Sumatakyo Onsen. Nagoya Station holds the record as the world’s largest and tallest train station (based on the size of its station towers)16

Nagoya is a major industrial centre and home to the headquarters of several prominant companies, including Toyota. It also serves as a key rail gateway to the Japanese Alps, making it an important transit point for travellers.17 For dinner, we sampled the local speciality, Hitsumabushi—a dish consisting of bite-sized pieces of grilled eel served over rice. We also enjoyed some eel sushi.

Steve Wide and Michelle Mackintosh, Train Japan: The Essential Rail Guide to Japan (Hardie Grant Explore, 2024) 154. ↩︎

Ibid. ↩︎

Ramsey Zarifeh and Anna Udagawa, Japan By Rail (Trailblazer, 5th ed, 2022) 168. ↩︎

Ibid 174. ↩︎

Ibid 177. ↩︎

Grand Tour of Switzerland in Japan, ‘Oigawa Railway - Brienz Rothorn Bahn (1977)’ (Embassy of Switzerland in Japan, online). ↩︎

Zarifeh and Udagawa (n 3) 174. ↩︎

Tim Gibson, ‘Japan’s $64BN Gamble on Levitating Bullet Trains Explained’ (The B1M, 18 August 2021, online). ↩︎

Paul J Ashton, How One Man Derailed Japan’s Future (LinkedIn, 7 March 2025). ↩︎

Ibid. ↩︎

Ibid. ↩︎

Ibid. ↩︎

Zarifeh and Udagawa (n 3) 178. ↩︎

Grand Tour of Switzerland in Japan, ‘Oigawa Railway - Brienz Rothorn Bahn (1977)’ (Embassy of Switzerland in Japan, online). ↩︎

Icarus Publishing, ‘The world of unexplored stations’ (2024) 84. ↩︎

Zarifeh and Udagawa (n 3) 203. ↩︎

Ibid 199. ↩︎