The West Highland Line links Glasgow with the ports of Mallaig and Oban. In March 2019, I took the route to Mallaig – a small fishing port in the Scottish Highlands from where one can catch a ferry to Armadale on the Isle of Skye. The train journey took approximately 5 hours and 30 minutes each way. First though, I had to travel an additional 5.5 hours from Oxford to Scotland.

Oxford to Glasgow

As the purpose of my trip was to take the West Highland Line, I stayed overnight in Glasgow so that my trip to Mallaig would occur during daylight hours. To get to Glasgow, I caught the train from Oxford, travelling via Birmingham and York. The rolling hills in Derbyshire were a particular highlight on this route.

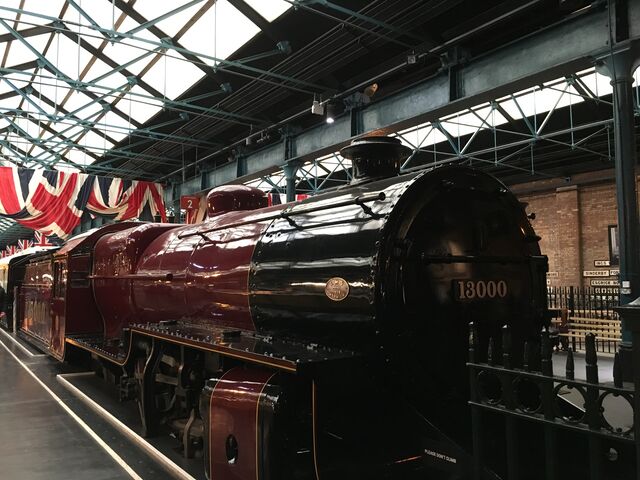

Before reaching Glasgow, I alighted in York where I enjoyed a visit to the National Railway Museum. The Royal Carriages exhibition in the Station Hall (a working railway building until the 1960s) was the standout. Here, I attended a talk about the royal carriages on display, and enjoyed hearing about the oldest preserved carriage in Europe (Queen Adelaide’s carriage), as well as the maximum protection carriage built for King George VI and the Queen Mother during World War II. In the Great Hall, I attended a talk about the Japanese bullet trains, before hopping on board the only train of this kind located outside of Japan.

West Highland Line

My trip on the West Highland Line commenced at Glasgow Queen Street Station. Opened in 1894, the West Highland Line travels through a wild landscape of lochs, snow capped mountains, and some of the smallest and most remote stations in the United Kingdom’s rail network. The Fort William – Mallaig extension of the route was opened in 1901. For one of the world’s most spectacular rail journeys, tickets are supremely affordable. For the 5.5 hour journey, I paid 11.10 GBP (with a 16–25 railcard). Although I did not have a guidebook dedicated to train travel in Scotland, my British ‘Railway Day Trips’ book did provide some useful information about the journey.

The train was surprisingly empty, with only a handful of passengers scattered throughout the carriages. Shortly after passing through Glaswegian suburbs, the train ran alongside Loch Lomond to the right and Gare Loch and Loch Long to the left. I found the latter particularly spectacular.

At Crianlarich, the train split in two, with the front carriages travelling to Oban and the rear two carriages to Mallaig. At first, however, there was very little direction as to which carriages people needed to be in to ensure they did not end up at the incorrect destination. After much confusion, an attendant finally came around (with mere minutes to spare), directing people to the correct carriages.

The horseshoe curve between Upper Tyndrum and Bridge of Orchy was another point of interest. The builders of the West Highland Line apparently did not have the money for a viaduct across the mouth of the broad valley, resulting in the famous horseshoe curve at the foot of Beinn Dorain (a mountain in the Bridge of Orchy hills).

Arriving at Bridge of Orchy, my guidebook informed me that the station is now used as a bunk house for hikers on the West Highland Way. I met one of these hikers on board the train. He alighted at Fort William, intending to hike south to Milngavie. I read that the route is normally completed in the opposite direction, with the easier southern stages preparing hikers for the more demanding northern sections.

Departing Bridge of Orchy, the line climbed to the vast and rugged wilderness area of Rannoch Moor. My guidebook informed me that the railway builders took five years to cross the moorland. Progress was held up by inhospitable winter weather conditions and labour disputes. In places, the builders had to ‘float’ the line on the moor, on foundations made from tree roots and ash. The next stop was Corrour, Britain’s most remote station which is located 16 kilometres from the nearest public road. My guidebook described it as ‘one of the loneliest spots on Britain’s rail network’. Corrour is also the United Kingdom’s highest altitude railway station, at 410 metres above sea level. Shortly after leaving Corrour, Loch Treig was visible on the left.

At Spean Bridge, the final stop before Fort William, I moved to a seat on the right-hand side of the train. I had done my research before commencing the journey and knew that for the segment of the route between Fort William and Mallaig, the left-hand side of the train would provide the best views. Importantly, I also knew that the train would change direction at Fort William. Anticipating the flood of people that would board at this station, I therefore took the opportunity to change seats. Fort William, the largest town on the West Highland Line, serves as the final destination for the Caledonian Sleeper from London Euston. As expected, scores of day-trippers boarded the train at Fort William and I was joined by three elderly people at my table seat. My new acquaintances were on an organised tour of the Scottish Highlands, and we enjoyed a nice chat as we watched the beautiful scenery roll past. The Fort William – Mallaig section of the route took approximately 1 hour and 23 minutes, passing through 11 tunnels.

Just prior to Glenfinnan station, the train crossed the Glenfinnan viaduct. My guidebook informed me that the structure consists of 21 arches. Sitting on the left-hand side of the train meant that I had great views around the curve, not only of the viaduct, but also of Glenfinnan Monument and Loch Shiel. For many people, this is the definite highlight of the West Highland Line, with the viaduct famous for featuring in the Harry Potter film series.

This was my second visit to Glenfinnan but my first time travelling across the viaduct. During the summer months, the heritage Jacobite steam train operates along the line between Fort William and Mallaig. In July 2014, I had the pleasure of visiting Glenfinnan and watching the passing train, as can be seen in the pictures below.

The final section of the route passed through Arisaig, the westernmost station in Britain. Running alongside the coast, there were great views of the Sound of Sleat, the islands of Rùm and Eigg, and the white sands of Morar.

Mallaig

I was loath to alight in Mallaig. The West Coast of Scotland was being pounded by a severe storm, although I was grateful that the wild weather only started about 5 minutes prior to the train’s arrival in Mallaig, meaning I was able to enjoy clear views throughout almost all of my journey. After eating lunch at The Fishmarket Restaurant, I attempted to complete a short circular walk around the village are surrounding hills, which I had read provided great views of the Isle of Skye. Unfortunately the weather hampered my efforts and I was forced to turn around. By this stage, the winds were so severe that it was nearly impossible for me to walk forward. Whilst I waited for the winds to die down, I took the opportunity to take some pictures of the picturesque fishing port.

The following morning I boarded the train, taking the West Highland Line in the opposite direction.

I changed trains in Glasgow, before taking a different route back to Oxford. This time, I travelled through the Lake District, changing trains for a final time in Wolverhampton. Highlights on this route included the Lake District’s vast green fields and rugged fell mountains.