The West Coast Wilderness Railway runs between the towns of Queenstown and Strahan in Western Tasmania. I took a trip on this railway in February 2023.

For those interested in train travel in Tasmania, it is worth noting that there are no scheduled passenger trains. The island’s mountainous terrain and dense rainforests pose considerable challenges for standard rail operations. Luckily, there are tourist trains available, the most famous of which is the West Coast Wilderness Railway on Tasmania’s rugged West Coast.

History of the Railway

The West Coast Wilderness Railway is a reconstruction of the historic Mount Lyell Railway, which commenced operation in 1899. The railway was originally built to transport copper from the Mount Lyell Mine in Queenstown to the port of Strahan. Amidst a global recession, thousands of workers from around the world made the long journey to Tasmania to work on the line. Fettlers and their families often lived in makeshift camps alongside the railway.1 At any given time, 500 labourers worked under harsh conditions to carve a path through dense rainforest.2 Workers faced relentless rain and freezing temperatures, alongside snakes and leeches in their boots.

The railway was a significant engineering achievement at its time. It was celebrated for its innovative use of the ABT rack-and-pinion system—designed by Swiss engineer Roman Abt—which allowed trains to ascend and descend steep grades while carrying heavy loads.3 The railway also played a heroic role during a 1912 fire in the Mount Lyell mine, swiftly transporting rescue equipment and personnel to save 170 men who were trapped underground.4

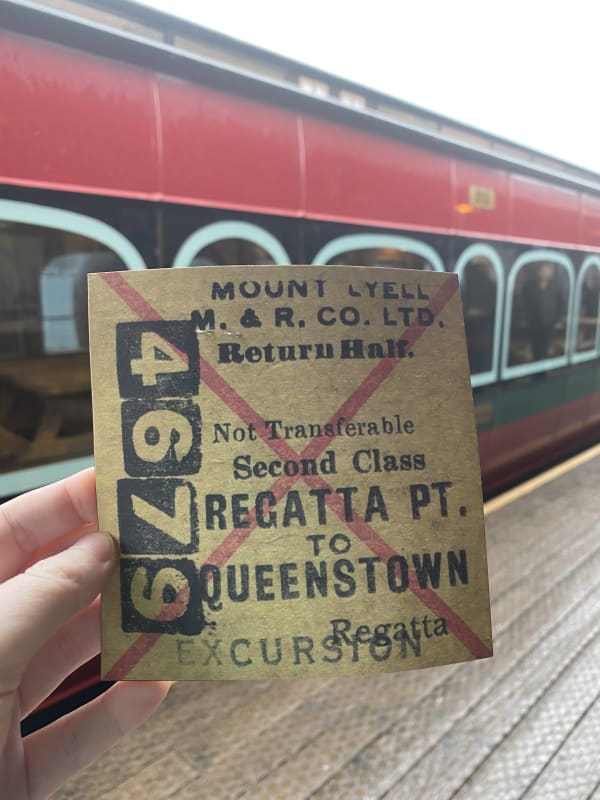

The railway was also pivotal to the beloved Mt Lyell picnics, an annual tradition that spanned over six decades. Beginning in 1897, the manager of the Mt Lyell mine, seeking to provide a respite for employees and their families from the mine’s demanding and polluted environment, organised a picnic on the banks of the King River. When the railway was extended to Strahan, the picnic was relocated to West Strahan Beach. Each year, excited residents of Queenstown boarded the steam train, dressed in their finest attire, eager for a day filled with music, food, and games. The train was often so crowded that passengers would end up riding in the open-air mine carts. In the early days, a brass band accompanied the train, and mothers would spend days baking pasties and cakes. Upon arrival in Strahan, festivities included gumboot throwing contests. The men often gravitated to a pub by the sea, with some becoming so inebriated that they would fall off the train on the return journey to Queenstown.5

As the costs associated with maintaining the railway soared, the Mount Lyell Mining and Railway Company shifted largely to road transport to move its copper. With the advent of improved highway access to the Mount Lyell Mine, the railway was finally closed in 1963.6 One locomotive and several carriages were donated to the Puffing Billy Railway in Victoria. You can read my post on the Puffing Billy Railway here. After falling into disrepair, significant refurbishment works were carried out on the Mount Lyell Railway and it eventually resumed full service in 2003. Today, the restored railway operates as a tourist attraction, featuring carriages crafted from Tasmanian timber which are reminiscent of the original Mount Lyell Railway carriages.7 The original locomotives still operate on the railway today.

The Route

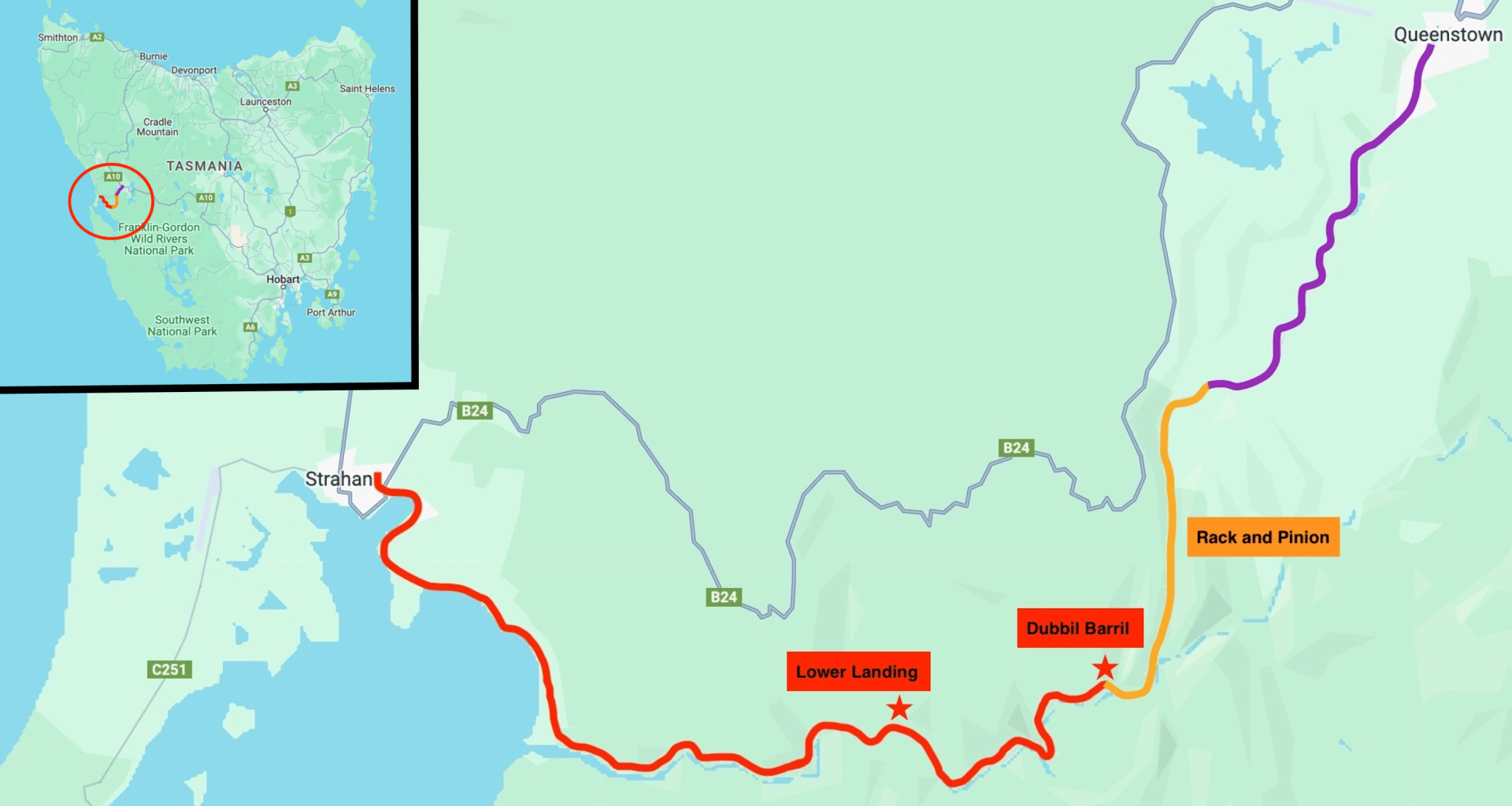

Prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, the railway offered four itineraries between Strahan and Queenstown, covering either the full route or segments of it. However, services were suspended during the COVID-19 lockdowns and operations had not yet been fully restored at the time of my visit in February 2023. The full route from Strahan to Queenstown remains suspended indefinitely due to limited rolling stock, staff shortages, and rising costs. At the time of my visit, two half routes options were available: the ‘River and Rainforest’ trip which is a round trip from Strahan to the halfway point of Dubbil Barril (see the red route on the map) and the ‘Rack and Gorge’ trip, covering the remaining section of the route as a return journey from Queenstown (shown in purple and orange on the map). The latter travels alongside the dramatic King River Gorge, on the only operating Abt rack-and-pinion railway in the Southern Hemisphere. Of course, we had originally booked the ‘Rack and Gorge’ excursion so we could experience the rack-and-pinion railway and the more mountainous terrain. However, about a month prior to our trip, the railway company called and informed me that due to maintenance works, they were not able to offer the ‘Rack and Gorge’ trip during the month of our visit. We were rebooked onto the ‘River and Rainforest’ trip, departing Strahan.

The five-hour return journey cost $120 and the service operated with a diesel locomotive. We were seated in the beautiful ‘Heritage Carriage’ which had comfortable, upholstered booth seating. A more expensive ‘Wilderness Carriage’ was also offered, although I preferred the aesthetic of our Heritage Carriage. Guests seated in the Wilderness Carriage are served Tasmanian sparkling wine and a series of small meals. There is also an open-air balcony section at the end of the Wilderness Carriage.

Departing Strahan’s Regatta Point Station, the train runs parallel to Macquarie Harbour before weaving into the temperate rainforests which cover Tasmania’s West Coast. In this part of the world, Huon pines grow alongside rivers and can live for up to 2,000 years.8

As the train follows the King River, it crosses several historic railway bridges, including the Iron Bridge at Teepookana. Over the course of the journey, stories are told of the railway’s history, the men who laboured to build the line, and their families who made a life in the rainforest.

At Lower Landing Station, passengers disembark to sample two distinct varieties of local leatherwood honey. Leatherwood honey is one of the world’s rarest honeys and is produced exclusively in Tasmania. It is made by bees that collect nectar from the Leatherwood tree, which grows in the western Tasmanian wilderness. Although I’m not typically a fan of honey, the tasting experience was still memorable.

Upon reaching Dubbil Barril, there is a 30-minute opportunity for a brief walk in the rainforest. Meanwhile, the engine is attached to the opposite end of the train for the return trip to Strahan.

For the return journey, passengers are instructed to switch sides with those directly across from them, ensuring everyone can enjoy the scenery from both sides of the track (not that there was much to see).

Although the Heritage Carriage was lovely and the scenery at the two stations where we alighted (Lower Landing and Dubbil Barril) was picturesque, the journey itself fell short. It is unfortunately one of the most boring train trips I have ever taken. The view from the windows was often unremarkable, and the experience was nowhere near as engaging as anticipated. I felt sorry for an enthusiastic group of elderly men in our carriage who spent the whole first half of the journey talking excitedly about the upcoming rack-and-pinion section. Apparently, they did not realise that the train would turn around at the halfway point of Dubbil Barril.

Since my visit, the company has introduced a handful of new tours, including two excursions departing Queenstown (one of which travels a three kilometre segment of the rack-and-pinion railway) and another excursion from Strahan to Lower Landing (which I would skip). The longer ‘River and Rainforest’ route that I took is currently suspended while upgrades are completed on the more remote sections of the railway line. The ‘Rack and Gorge’ experience is also currently on hold for the same reason.

Overall, I cannot recommend the portion of the West Coast Wilderness Railway travelling between Strahan and Dubbil Barril, unless you have a particular interest in beautiful train carriages. While I can’t speak to the ‘Rack and Gorge’ route as I was unable to travel on it, I imagine it easily surpasses the journey between Strahan and Dubbil Barril. I will have to return on a future trip to Tasmania to experience this segment of the route.

Other Train-Related Attractions in Tasmania

There are a small number of other train experiences in Tasmania. We particularly enjoyed a visit to ‘Railtrack Riders’, located about an hour west of Hobart in southern Tasmania. This was a pedal-powered rail car journey through the temperate rainforest on a historic rail line. Our trip from Maydena to Pig & Whistle was an 8 kilometre return journey that took about 1.5 hours. Pedalling the rail car uphill was quite strenuous. There were two other couples on our trip, in addition to the guide. One elderly couple astonishingly managed to speed ahead, leaving us struggling to keep up. In fact, we were so slow at times that the ATV rail vehicle which follows behind had to give us a push up the hill. The journey took a memorable turn when we caught up to the elderly couple, who had stopped to let an echidna cross the tracks. Our guide gently nudged the echidna along, and we continued on our way.

We also explored the Margate Train, located about 20 kilometres south of Hobart. This unique attraction features a variety of shops and cafes—including an arts and craft store, a microbrewery, and a pancake parlour—all housed within former Tasmanian Government railway carriages.

David Bowden, Great Railway Journeys in Australia and New Zealand (John Beaufoy Publishing, 3rd ed, 2023) 106–7. ↩︎

Ibid 107. ↩︎

Ibid. ↩︎

Max Wade Matthews, The World’s Great Railway Journeys (Anness Publishing Ltd, 2011) 239. ↩︎

ABC Northern Tasmania, ‘Mt Lyell Strahan Picnic celebrating 125 years’ (25 January 2023). ↩︎

Bowden (n 1) 107. ↩︎

Ibid. ↩︎

Sarah Baxter, History of the World in 500 Railway Journeys (Quarto Publishing, 2017) 67. ↩︎