Zell am See to Graz

After an enjoyable few days in Zell am See, I commenced my journey towards Vienna, travelling via Bischofshofen, Graz, and the famous Semmering Railway. It is possible to ride the Transalpin train all the way from Zurich to Graz (refer to my previous post on this special panorama train). However, there is only one Transalpin train per day and I did not have time to wait for its afternoon arrival into Zell am See. Instead, I travelled between Zell am See and Vienna on a number of regular commuter trains.

The first two trains transported me between Zell am See and Graz, with a transfer in Bischofshofen. This journey took 4.5 hours. The railway follows the River Salzach for the majority of the journey between Zell am See and Bischofshofen. The below images show the view from the train.

Bischofshofen is a town in the district of St. Johann im Pongau in the Austrian state of Salzburg. I had about 30 minutes at the station before transferring to my next train.

After departing Bischofshofen, the railway travels alongside the Fritzbach River before passing the village of Hüttau. Its Parish Church, constructed in 1472, and the Talübergang Larzenbach (a twin span viaduct) are visible from the train (both pictured below). Another notable sight en route is Trautenfels Castle which stands at the foot of the Grimming (an isolated peak in the Austrian Alps). The castle was constructed during the medieval period, sometime prior to 1260. The below images show the views from the train between Bischofshofen and Graz.

Graz

Graz is the second-largest city in Austria and is known for its historic old town which is one of the best-preserved city centres in Central Europe. The city has assimilated a multitude of influences from its neighbouring regions of Central Europe, Italy, and the Balkan countries. I had about 5-hours in Graz before boarding my next train to Vienna. Although trains operate hourly between Austria’s two largest cities, I opted to spend some time exploring Graz before proceeding with my journey.

I enjoyed walking around Graz’s Old Town and was particularly impressed by the Town Hall with its neoclassical façade (pictured above). Located on the main square, the Town Hall was constructed between 1890 and 1893. Trams have operated throughout the city since 1878 when the first horse tramway was put into operation.

I also enjoyed visiting the Graz Schlossberg: a 123-metre dolomite rock situated in the centre of the city. The clock tower on the Schlossberg dates back to the 16th-century. There are expansive views of the city from the top of the Schlossberg. Visitors can reach the top via a staircase, a glass lift that ascends inside the mountain, or a funicular railway. The funicular railway has transported passengers to the top of the Schlossberg for over a century and the journey takes less than 2-minutes. I opted to climb the staircase, however, had I known about the funicular railway, I would have certainly selected that option. Underneath the Schlossberg lies an extensive network of tunnels constructed to safeguard the population of Graz from aerial bombing during World War II (pictured above).

The Semmering Railway

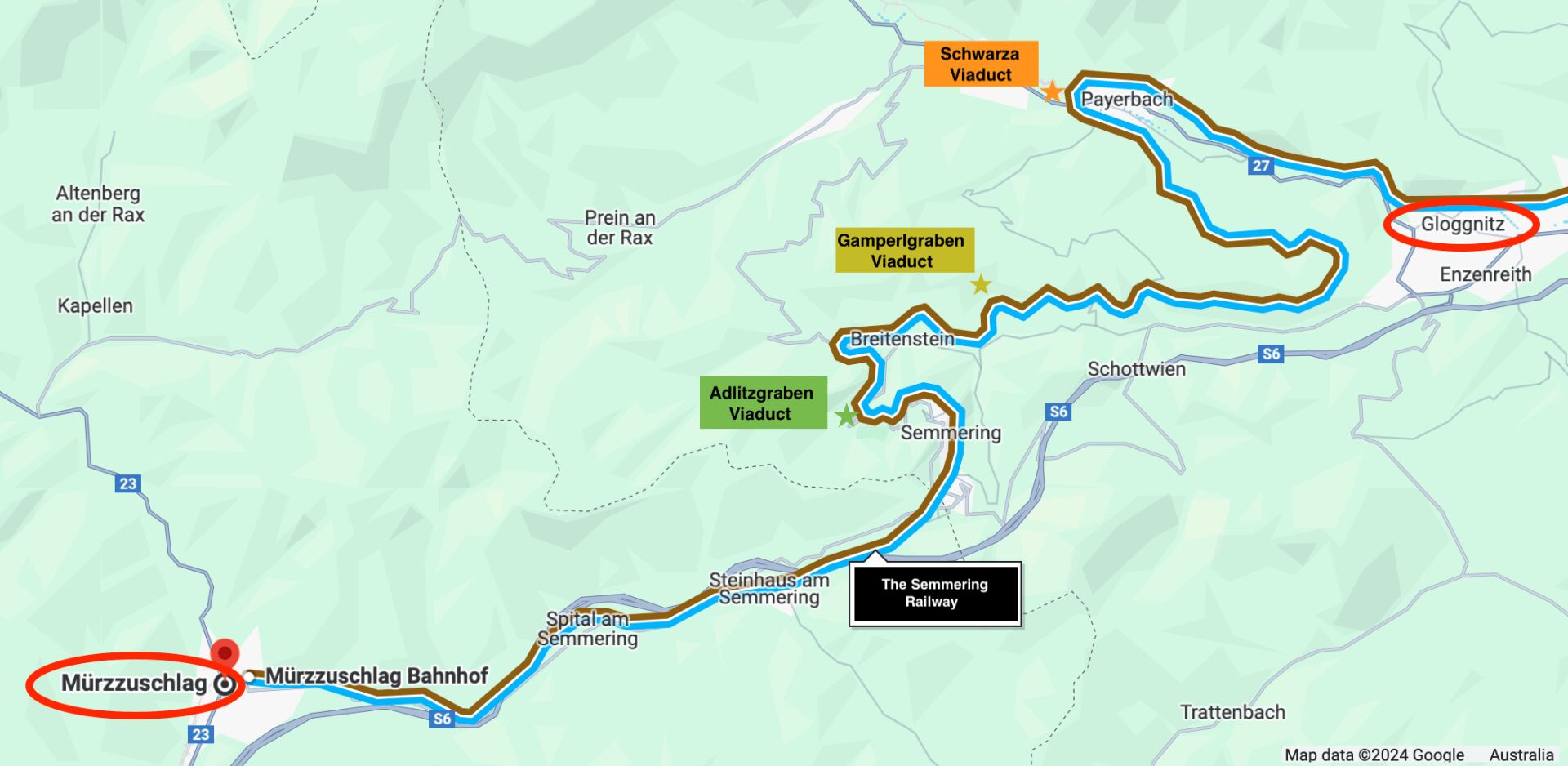

After an enjoyable afternoon in Graz, I returned to Graz Station where I boarded a train to Vienna; a train that would carry me across the UNESCO world-heritage listed Semmering Railway! The train between Graz and Vienna took just over 2.5 hours, with the 42-kilometre section of track that connects the towns of Mürzzuschlag and Gloggnitz known as the Semmering Railway. Constructed in 1854, the Semmering Railway traverses 16 viaducts, 14 tunnels, 11 iron bridges, and over 100 stone bridges. Some of the viaducts have two-storey arches which are needed to bridge the plunging valley. The best views are from the right-side of the train when travelling in the direction of Vienna.

The railway was constructed as part of a plan to connect Vienna with the Adriatic port at Trieste—the “Austrian Riviera”—which was known for its prestige and prosperity during the 1830s.1 The stretch of track between Vienna and Gloggnitz opened in 1841, and the section linking Graz and Mürzzuschlag was completed in 1844.2 This left the difficult mountain range in the middle (between Gloggnitz and Mürzzuschlag). Connecting these two towns in order to unite both sections of track proved problematic. Indeed, many engineers were of the view that it was simply impossible for adhesion locomotives to operate on such a steep and demanding route. Alternatives, including horse-drawn trams, were considered. However, engineer Carl Ritter von Ghega took inspiration from the mountain railways of the United States. He visited America to inspect these railways in person, before bringing his newly-acquired knowledge back to Austria.3

An innovative type of locomotive was then commissioned to cope with the difficult mountain terrain. A competition was held to help design this new locomotive, but when none of the four entries were deemed suitable, a fifth option was commissioned, incorporating the best elements of all four designs.4 Twenty-thousand workers were enlisted for the construction of the Semmering Railway. This was tough work, compounded by the absence of powerful explosives to aid the tunnelling process.5 The most demanding section of track was between Gloggnitz and the Semmering summit tunnel at a height of 1,431 metres. At the time, no railway had ever been built as high.6 The death toll during construction was somewhere between 700 and 1000 workers, mostly due to the effects of typhus or cholera, although some fatalities were also attributed to falling rocks.7

Once completed, the Semmering Railway was among the earliest railways in Europe to ascend a major mountain grade. As the route was not electrified until 1959, steam locomotives were required to lift trains over the difficult mountain terrain for over 100-years.8 The Semmering Railway was eventually added to the UNESCO World Heritage List in 1998 as ‘one of the greatest feats of civil engineering during the pioneering phase of railway building’.9

When you look up images of the Semmering Railway, with its double-arched viaducts and long sections of track that hug the mountainside, it certainly looks spectacular. However, I found that the views from the train itself were far from impressive, especially compared to the much more spectacular rail journeys I had been on earlier in the week in other parts of Austria. It would seem that the Semmering Railway’s impressive viaducts are perhaps best viewed from outside the train.

The train was also extremely crowded; a far cry from the spacious and empty panoramic and first-class trains I had grown accustomed to over the previous week. I was seated next to a teenage girl who seemed very confused as to why I was taking so many photos out the window. Given that the lacklustre views did not improve over the course of the journey, her bewilderment was understandable. I found it very entertaining when she herself started to take some pictures out the window, albeit in a very disinterested manner, fearing perhaps that she was missing out on something significant.

Unfortunately, during my time in Graz, the weather had taken a turn for the worse, and my experience on the Semmering Railway was a very rainy one. Although the weather did not really impact the views from the train, it did impede my ability to take high-quality photos. One particularly disappointing image shows the train winding around a bend on one of the Semmering Railway’s famous viaducts (the Adlitzgraben Viaduct which is 151-metres long and 24-metres high!) Regrettably, my camera focussed on the raindrops on the window, resulting in a blurred image of the train and viaduct. It would have been a spectacular shot in more favourable weather conditions!

As the railway descended steeply toward Semmering, it wound through several horseshoe curves and over numerous arched stone viaducts. Semmering was a well-known resort town until the 1930s, but never recovered after World War II.10 There were great views as the train travelled over the Gamperlgraben Viaduct, which is 152-metres long and 37-metres high. The railway then crossed the River Schwarza on the impressive Schwarza-Viaduct. Spanning 276-metres in length, this is the longest viaduct on the line. Continuing its journey east, the train navigated an enormous horseshoe curve as we approached Payerbach Station. My guidebook informed me that Payerbach is a quaint Austrian village that provides an interesting interlude for travellers seeking an overnight stay.11

After a disappointing train journey,12 I alighted in Vienna’s Central Station. I only had one night in Vienna. Having been to this city on a previous trip, this was just a quick overnight stop before continuing my journey into Poland the following morning.

Travel on the Semmering Railway to experience a historically rich journey, but temper your expectations for breathtaking views. You should also consider taking this route before it is too late! A base tunnel is currently under construction between Gloggnitz and Mürzzuschlag. When completed in 2030, the tunnel will completely bypass the original Semmering crossing.13

BBC, Great Continental Railway Journeys (Simon & Schuster UK, 2015) 191. ↩︎

Ibid 190. ↩︎

Insight Guides, Insight Guides Great Railway Journeys of Europe (APA Publications, 2nd ed, 2019) 243; BBC (n 1) 193. ↩︎

BBC (n 1) 193. ↩︎

Ibid 191. ↩︎

Ibid. ↩︎

Ibid 193. ↩︎

Brian Solomon, The World’s Great Rail Journeys (John Beaufoy Publishing, 2nd ed, 2022) 63. ↩︎

BBC (n 1) 192. ↩︎

Insight Guides (n 3) 243. ↩︎

Solomon (n 8) 64. ↩︎

Just kidding…kind of. While all train journeys are extremely exciting, this one did fail to meet my expectations. ↩︎

See ÖBB, ‘Semmering Base Tunnel’ (online, 2024). ↩︎