‘Without its railways and the men who built them, modern confederated Canada would probably not exist.’1

In June 2024, my travel companion and I travelled on The Canadian—one of the world’s most spectacular train journeys! This transcontinental passenger train connects Vancouver and Toronto and covers a distance of 4,466 kilometres, making it one of the longest train journeys in the world. Passengers completing the full route spend four nights on board the train. Regrettably, our trip was much shorter. We travelled from Vancouver to the Canadian Rockies, a distance of just over 1,100 kilometres by rail. This journey took approximately 28 hours, including 5 hours worth of delays (more on that later). Along the way, we were treated to breathtaking scenery, from turquoise lakes and rivers, to majestic snow-capped mountains.

History of the Railway

The story of Canada’s transcontinental railway is a dramatic tale of ambition, loss, and national unity. The Canadian Pacific Railway (CPR) was instrumental in stitching together a sprawling country. As stated by my guidebook, the CPR didn’t just build the tracks; it built a nation.2 The saga began in 1867 with the formation of the Dominion of Canada. Despite this political milestone, British Columbia remained under the jurisdiction of Great Britain, the westernmost province cut off from the burgeoning confederation.3 At that time, Canada lay in the shadow of a formidable neighbour: the United States, which had a booming population of approximately 40 million, compared to Canada’s mere 3.5 million people. The U.S. had been aggressively pursuing annexation for several years, leaving Canada feeling vulnerable. Sir John A Macdonald, Canada’s first Prime Minister, was convinced that for Canada to survive, it needed to secure British Columbia.4

The Canadian government’s promise to build a railway across the Rocky Mountains within a decade was the key to enticing British Columbia to finally join the confederation in 1871.5 Before the railway could be built, however, Prime Minister Macdonald was charged with corruption in Parliament, following allegations of bribery related to the construction of the railway. The government was dissolved in 18736 and new leader Alexander Mackenzie found himself burdened with a railway project which he had previously denounced as ‘an act of insane recklessness!’7 Mackenzie even attempted to scale back the ambitious project by proposing a shorter railway that would use steamships to cross the Great Lakes.8 Compounding the challenges, the Indigenous population in Manitoba actively opposed the railway, viewing it as a new form of colonial oppression.9

In the end, however, Macdonald returned to power and a continuous transcontinental railway was built. This was certainly no small feat. The sheer scale of the project and challenges posed by Canada’s geography and climate made progress painfully slow.10 Construction of the railway by the CPR required the labour of 12,000 men, which included a substantial contingent of Chinese workers, alongside 5,000 horses and 300 dogsled teams.11 Workers faced extreme challenges: blasting tunnels through the Rocky Mountains, crossing treacherous stretches of river, and enduring harsh weather conditions (including temperatures plummeting to minus thirty degrees Celsius). A man per mile is reported to have died blasting the route through the Rockies and traversing the more treacherous stretches of the Fraser River.12 Life along the line was also frequently disrupted by the workmen’s enthusiasm for liquor. A railway worker’s life was particularly harsh and for many, whisky was a much-needed diversion.13

The railway was completed in 1885, linking Vancouver to Montreal, via Banff and Calgary. The first transcontinental passenger train ran to Port Moody (located 20km from Vancouver) in 1886, and the first train to Vancouver arrived in 1887. The railway was pivotal in facilitating the movement of European immigrants to the Prairies, with the CPR launching extensive promotional campaigns to entice newcomers to purchase Canadian land.14 The trains that ran on the newly laid tracks were designed with luxury in mind. They featured opulent sleeping cars that even included bathtubs.15 The restaurant cars were adorned with elegant decor and fine crystal and silver.16 There were also outside viewing cars designed for open-air sightseeing in the Rockies.17 However, the railway was constructed too quickly and lacked tunnels to ease some of the sharper inclines, causing the locomotives to race down gradients that were twice as steep as what is typically considered acceptable. In these conditions, the restaurant cars effectively became unusable, as crockery, glasses, and cutlery went flying. Eventually the restaurant cars were uncoupled and left at the bottom of inclines where they served as new ‘dining stations’.18

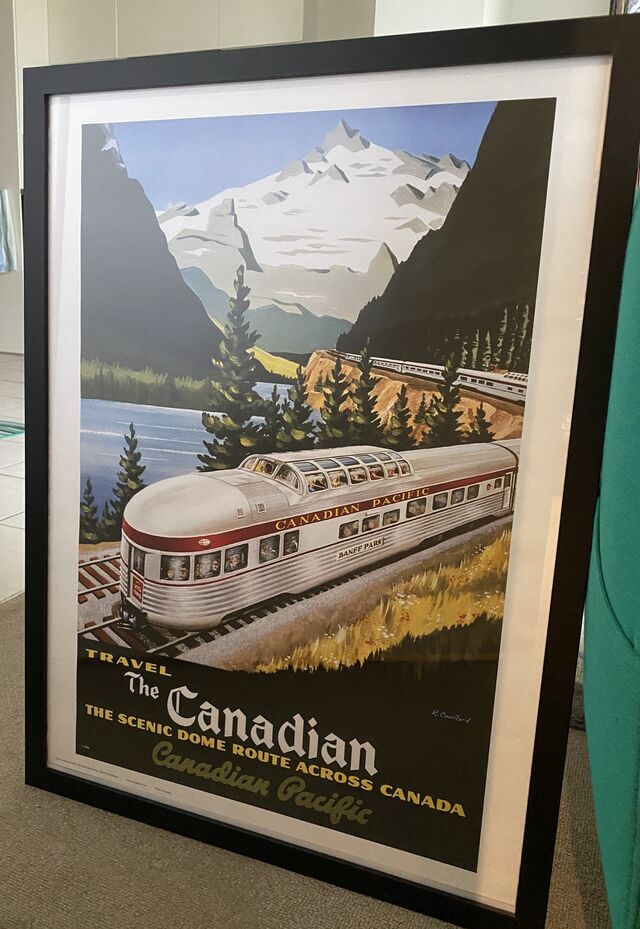

As entrepreneurs rushed to emulate the success of the CPR, the Canadian National Railway (CNR) emerged as its direct competitor.19 In 1915, the CNR established an alternative transcontinental route that ran north of the CPR’s path, connecting Vancouver and Toronto via Jasper and Edmonton. However, as the 20th century progressed, passenger traffic steadily declined, especially after World War II. Motor vehicles were becoming the dominant form of transportation, and air travel was increasingly affordable.20 In a bid to attract passengers, both railway companies launched faster, upgraded services.21 In 1955, CPR unveiled its luxurious new offering: The Canadian. This train showcased futuristic stainless-steel carriages with observation domes.

By 1967, there were four transcontinental trains operating each day!22 The completion of the Trans-Canada Highway, however, ultimately resulted in the takeover of passenger trains by a government corporation, VIA Rail, in 1978.23 VIA Rail consolidated the passenger services of the two railway companies, though both the CPR and CNR continue to operate freight services (more on this later). VIA Rail abandoned the southern route via Calgary and Banff in 1990, leaving the northern route (via Edmonton and Jasper), as the only remaining transcontinental passenger line.24 This marked the end of over a century of regular service along the CPR’s historic original tracks.25 Instead of acquiring new carriages, VIA Rail invested over 200 million dollars in completely upgrading The Canadian’s original stainless steel carriages, making this train a classic in its own right, despite the fact it now operates on a different company’s route.26 There are now no regular passenger services at all on the original CPR tracks via Calgary and Banff, other than the Rocky Mountaineer luxury tourist train which operates several routes across the Rockies. That said, the eastbound train which we took from Vancouver still travels along a segment of the original CPR line through the Fraser and Thompson Rivers between Vancouver and Kamloops.

VIA Rail’s current operations of The Canadian include a thrice-weekly service during the peak season (May to October) and a twice-weekly schedule from October to April.

Vancouver

We had exactly 24 hours to spend in Vancouver before boarding The Canadian. Long-time readers of this train blog may recall that I briefly visited Vancouver in 2019 when I took a short detour into Canada during my 220 hour train adventure around the USA. It may be recalled that I did not particularly enjoy Vancouver on my first visit, mainly due to my dislike of the city’s unsightly modernist architecture. My opinion did not change during my second visit. In fact, not only did I find Vancouver uglier than ever, I found the smell of weed permeating every street in the city to be almost unbearable. The city’s serious homelessness issue also appears to be worsening and it is almost impossible to find a hotel room in the city centre for under $600 per night during the summer months.

Having given it a second chance, I’m afraid I can now confidently declare Vancouver to be the worst city that I have ever visited. I must respectfully disagree with the observation from my guidebook that ‘few cities could match the scenic delights along the route of the Canadian, but Vancouver does, with its glorious position overlooking the sea and the North Shore Mountains’.27 While the city’s mountain backdrop is undeniably stunning,28 even my profound love for mountains does not alter my view. This really just underscores how utterly unappealing the city is. Readers are advised to minimise their time in Vancouver and instead visit the picturesque alpine village of Whistler which is located about two hours away by bus (I escaped Vancouver and did exactly this on my previous trip which you can read about here).

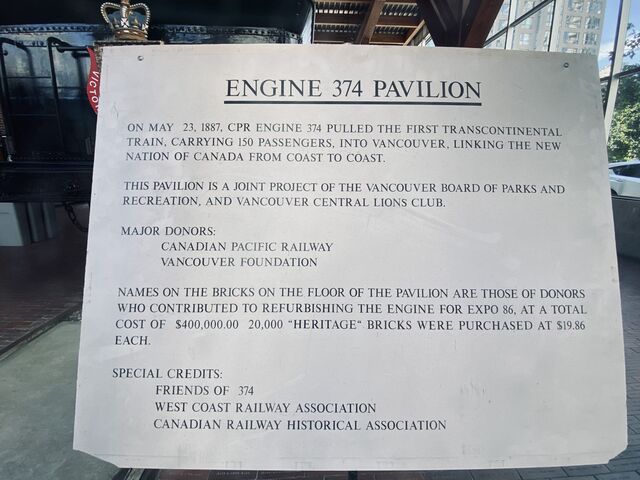

We did manage to find two exciting attractions in Vancouver. The first was Engine No 374: the Canadian Pacific Railway locomotive that pulled the first ever transcontinental passenger train across Canada in 1887. After many decades of service, Engine 374 was retired in 1945 and sent to Vancouver. It was proudly displayed at Kitsilano Beach, where the public was able to admire and interact with the engine. However, over the following decades, the engine remained on the beach, neglected and forgotten. It fell victim to rust, vandalism, and the harsh elements of the seasons, with its condition deteriorating under the relentless salt air. But hope was not lost! A passionate group of volunteers stepped in, determined to restore the engine to its former glory. Their efforts were supported by the innovative ‘Heritage Brick Program’ which raised an impressive $400,000. Today, Engine 374 shines anew at the Vancouver Engine 374 Pavilion, which welcomes visitors from 10 AM to 4 PM during the summer months. The pavilion floor is adorned with bricks engraved with the names of individuals who purchased a brick for approximately $20 through the Heritage Brick Program. The restored locomotive stands as a testament to the community that rallied behind its revival.

The second Vancouver attraction worthy of mention was the Old Spaghetti Factory in Gastown where we dined in an old tram carriage! Not only was the setting excellent but the prices at this place were also unbeatable. If you order the “it’s all included” you will receive a plate of hot sourdough bread served with a whipped garlic butter (this was the best butter I have ever tasted!), a large bowl of your choice of spaghetti (I went for the browned butter and mizithra cheese), spumoni ice cream for dessert, and a nice cup of tea (or coffee) to finish off. Prices start at about $15 (depending on your choice of spaghetti). Even with the tax and tip, this was an absolute bargain! Shockingly, the tram carriage was largely empty, with most diners appearing content, for some unknown reason, to sit elsewhere in the restaurant.

On board the train

The following day we made our way to Vancouver’s Pacific Central Station to commence our journey on The Canadian!

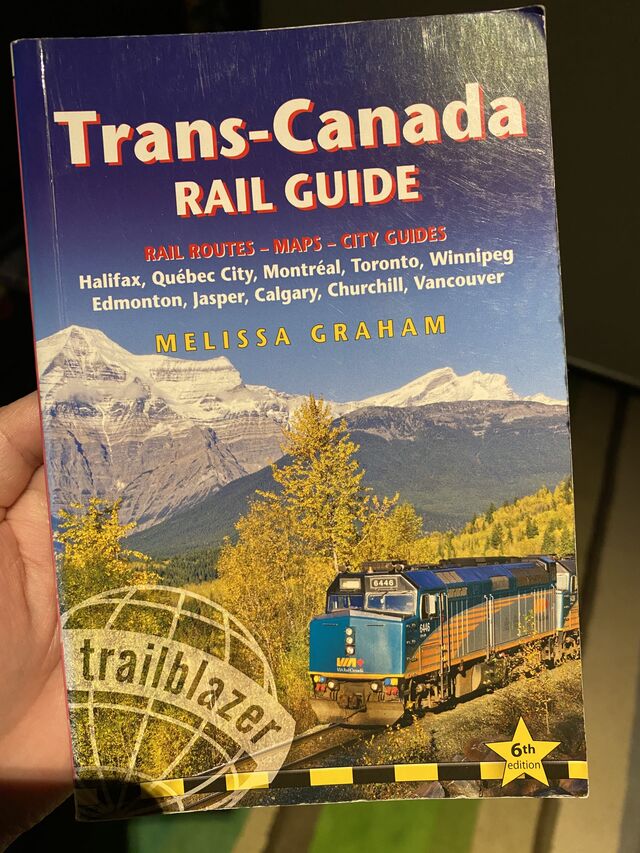

All of VIA Rail’s long-distance trains include a baggage car, where passengers can check-in luggage for the duration of their journey. We arrived at the station approximately 60 minutes before departure to do so. My guidebook for the trip was Trailblazer’s Trans-Canada Rail Guide which includes a very useful mile-by-mile route guide, in addition to a fascinating section on the history of Canada’s transcontinental railway.

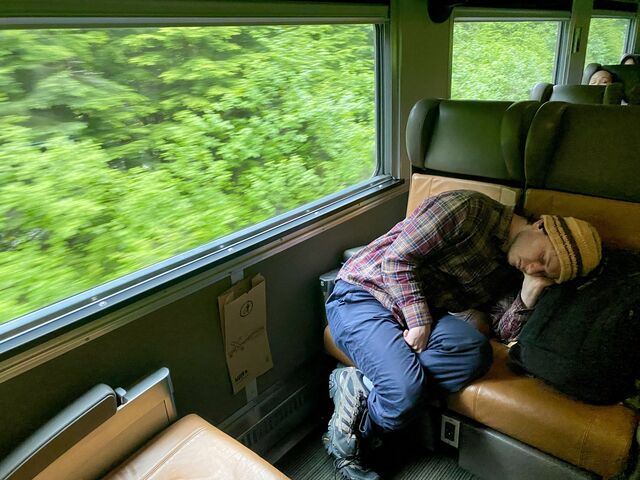

Economy class passengers on The Canadian enjoy roomy, reclining seats with leg rests. My travel companion and I were placed in a four-seat configuration (two seats directly across from another two) which provided ample space. The carriage attendant, aware that we would be travelling overnight, assigned us to this spot during boarding.

For those who prefer not to spend the night in a regular seat, The Canadian offers various sleeping accommodations. Berths feature wide double seats that convert into bunk beds at night and are equipped with heavy curtains for added privacy. Additionally, there are cabins (or ‘roomettes’) available for one or two people. However, the cost for a single night’s sleep is very steep. For my travel companion and I to book a berth (the most basic sleeper option) it would have cost over $1,000 CAD per person for just one night. In comparison, our economy class tickets were $190 CAD for the 28 hour journey. I’ve had my eye on The Canadian for several years and know that, at least during the winter months, you can sometimes secure a sleeper ticket for the full route (4 nights from Vancouver to Toronto) for around $800 CAD in total. In the summer, though, travelling for just one night between Vancouver and Jasper is apparently considerably more expensive.

It should also be noted that a ticket price of $190 for The Canadian is substantially more affordable than a ticket for a one night journey on the luxury tourist train, the Rocky Mountaineer, which travels over these exact same rail tracks. While the Rocky Mountaineer offers several routes across British Columbia and Alberta, the price of its Vancouver to Jasper trip starts at about $3,000 in the summer months for even the most basic class of service.

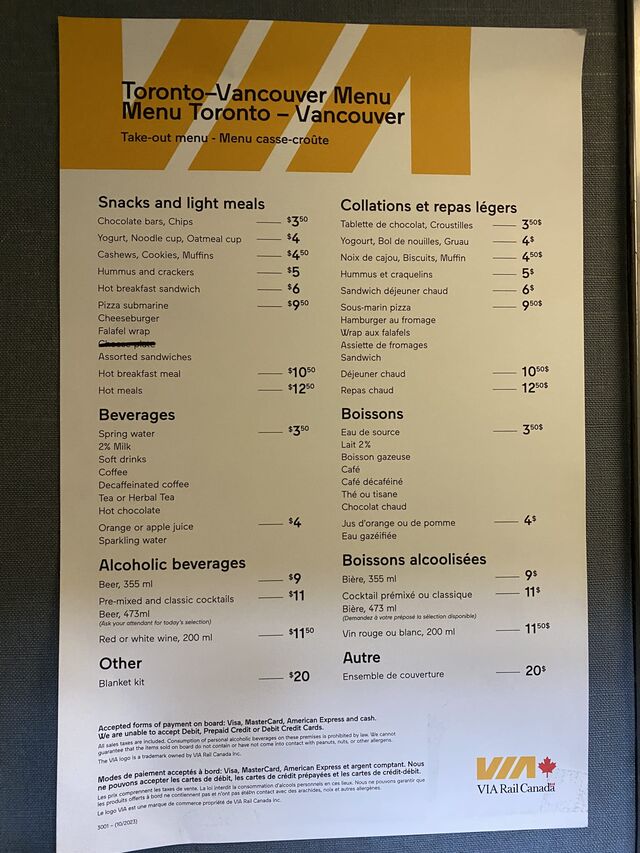

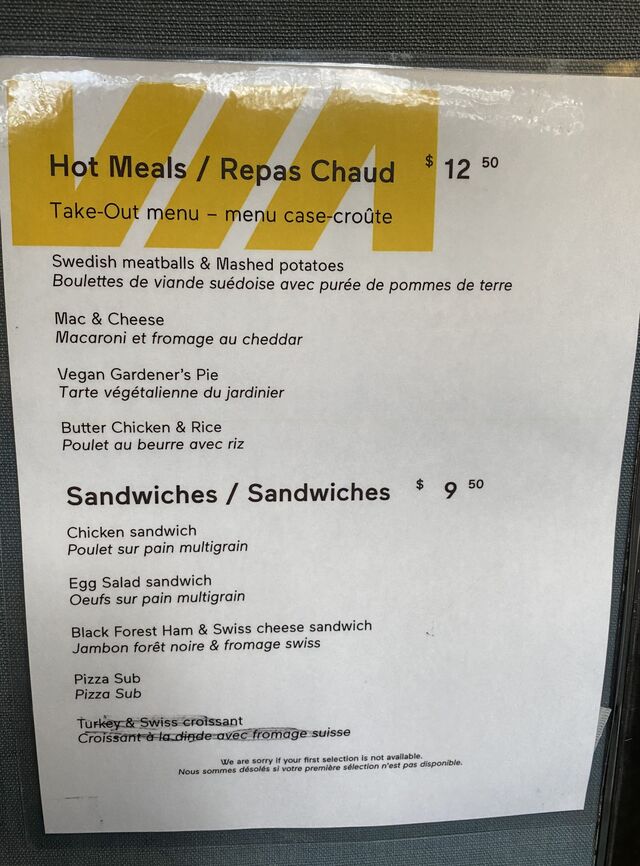

For ‘sleeper plus’ or ‘prestige’ passengers on The Canadian, all meals are included in the price of the ticket. As we were travelling in economy class, however, we had to sort out our own food. The lower section of the skyline car consists of a kitchen and café-style seating area with tables and chairs, as well as a food counter where passengers can purchase snacks and meals. It is advisable to bring cash for food and drinks, as although credit and debit cards are accepted, the internet connection can be unreliable in remote areas, potentially making card payments difficult.

There is also a separate lounge area in the lower section of the skyline car. Upstairs, passengers will find the observation dome, with its wrap-around windows which provide panoramic views of the beautiful landscape. Economy class passengers have access to their own observation dome, separate from the one designated for sleeper class passengers. However, it’s worth noting that the observation dome was extremely cold, which deterred many passengers from spending much time there. Readers are advised to bring a few jackets.

Travellers, take note: significant delays on The Canadian are a common occurrence. Freight trains, operated by the Canadian Pacific Railway and the Canadian National Railway which own the tracks, take precedence over passenger services on the line. VIA Rail, which operates The Canadian, owns a mere three percent of the 12,000 km of rail lines it uses and must pay user fees to CPR and CNR. As a result, The Canadian must stop and wait for freight trains to pass, which on our journey, led to delays of up to 90 minutes at a time. Freight trains haul vital cargo like coal, sulphur, potash, and grain. Westbound trains, often stretching for miles, gather wheat from the Prairies for export, while eastbound trains transport imported vehicles to the northeastern USA.29 The delays used to be so severe that The Canadian would regularly fall 12 to 20 hours behind schedule. Thankfully, in early 2019, VIA Rail revised its timetabling to better handle freight disruptions. While these adjustments apparently made a notable difference,30 our journey to Edson was still delayed by over 5 hours, with our scheduled arrival time of 3:19 PM being pushed to around 8:30 PM.

In response to these ongoing issues, the Rail Passenger Priority Bill proposes to amend the Canada Transportation Act (1996) to give passenger trains priority. The Bill was introduced by a Canadian politician who experienced these delays first-hand. He noted that his journey from Toronto to Vancouver took about a day longer than it would have 50 years ago due to frequent freight train interruptions.31 Concerns linger in the shipping and freight industries about how such regulations might affect the supply chain. Meanwhile, in the United States, Amtrak has enjoyed a right of way for about 50 years, granting passenger trains priority. However, as will be recalled from my U.S. train blog series, this priority does not appear to translate into fewer delays, due to insufficient enforcement by the Department of Justice. That said, I do not recall any of my U.S. train journeys experiencing delays that were as frequent or as lengthy as those on The Canadian. Of course, more delays means more time on the train and that’s hardly the worst thing in the world!

Vancouver to Jasper

As The Canadian left Vancouver, the urban landscape slowly gave way to impressive natural scenery.

All eastbound trains travelling from Vancouver to Kamloops use the original CPR tracks on the western side of the Fraser River for the first part of the journey. Early stops included the city of Mission, which my guidebook informed me was the site of Canada’s first train robbery. In 1904, a CPR train fell victim to a daring robbery orchestrated by the notorious sixty-year-old Billy Miner, alongside his accomplices, Shorty Dunn and Jake Terry. Their haul included an impressive $7,000 worth of gold dust. To evade capture, they rowed across the Fraser River and then made their escape on horseback toward the U.S. border.32

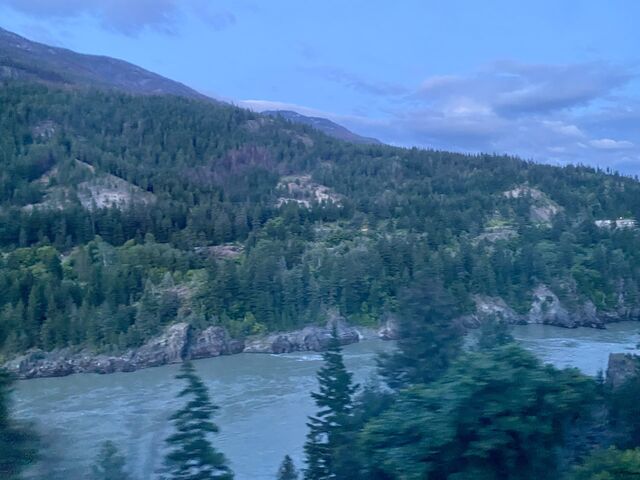

The scenery along the Fraser River was particularly striking. The river carves its way through a deep canyon, between the Lillooet Ranges on its west and the rugged Cascade Range to the east. Hells Gate is a famous portion of the canyon where the walls close in dramatically, forcing the river through a narrow gap of only 35 metres. My guidebook instructed me to spare a thought for the millions of salmon who don’t enjoy a smooth ride on their way to the Pacific Ocean; apparently only about a quarter of them make it.

Darkness fell just before we arrived in Lytton at around 9:45 PM. It was late in the night when the train pulled into the city of Kamloops.

After approximately three hours of sleep on the train, I awoke at 4:30 AM the next morning near the community of Little Fort.

The train skirts the North Thompson River for quite some time, before approaching Pyramid Creek Falls. An announcement encourages passengers to look out the window and admire the breathtaking sight of the falls cascading 90 metres from a lake on Mt Cheadle and tumbling toward the tracks.

Shortly after, the majestic Rocky Mountains come into view, with the snow-capped peaks of the Premier Range rising before us. These 11 peaks are named after Canadian and British prime ministers.

The real showstopper is the imposing Mt Robson, standing tall as the highest peak in the Canadian Rockies at 3,954 metres. The observation car, with its panoramic windows, offers unobstructed views of the impressive peaks.

Before long, the train is travelling alongside the green waters of Moose Lake which reflect the passing train and surrounding mountain peaks. My guidebook informed me that the lake is a favoured watering spot for moose. Enjoying our lunch alongside the lake was a standout moment of the trip.

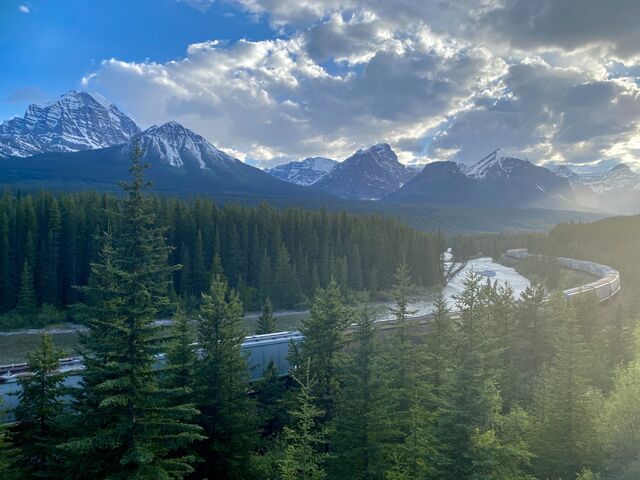

This section of the route also provided a great photo opportunity as The Canadian travelled around a bend alongside Moose Lake.

Next is Yellowhead Lake and the Yellowhead Pass, the latter of which provides a natural corridor through the continental divide. This divide traces the main ranges of the Rocky Mountains, marking the point where rivers on one side flow west toward the Pacific Ocean, while those on the other drain into the Arctic or Atlantic Oceans. It also serves as the border between Alberta and British Columbia.

The most interesting character we encountered during our journey on The Canadian was a middle-aged woman who boarded the train with her friend in the dead of night in Kamloops. Their dynamic was intriguing. They were either old friends, reuniting after decades apart, or perhaps new companions who had recently decided to embark on this adventure together. Either way, they were clearly unfamiliar with each other, but were relishing their newfound or rekindled bond. Throughout the journey, the middle-aged woman engaged us in intermittent conversation, even going so far as to join us in our seats on our side of the train. This behaviour was a bit strange, but I thought she was friendly enough. My partner, however, was picking up some strange vibes from her.

A dramatic moment unfolded a few hours before the train reached Jasper. The woman casually revealed to her travel companion that she had made multiple bookings for their accommodation in Hinton, essentially securing at least three reservations for the same hotel. This revelation irritated her friend, who was keen to resolve the situation and avoid paying for the same room three times, but the middle-aged woman remained blissfully indifferent, seemingly oblivious to the gravity of the problem. Her friend insisted she call the booking websites to cancel, but each time the friend directed her to ask a crucial question (e.g. “can we please cancel the booking?”), the middle-aged woman froze, unable to act. By the time we rolled into Jasper, the fragile threads of their newfound friendship were in tatters, leaving a palpable tension hanging in the air.

Jasper

The Canadian arrived in Jasper three hours behind schedule. Nestled deep within the Canadian Rockies along the banks of the Athabasca River, Jasper is located in the largest national park in the Rockies: Jasper National Park. My guidebook described Jasper as a quieter, more intimate alternative to the bustling Banff.

Constructed by the Canadian National Railway in 1925, Jasper’s railway station is a rustic building, complete with a beamed roof and art-deco travel posters. Stepping off the train was breathtaking, as the charm of Jasper enveloped us. We felt completely surrounded by the towering mountains rising on all sides.

The train paused for an hour, giving us time to explore the 1923 locomotive situated outside the station, as well as sample a Canadian delicacy: Tim Hortons. Tragically, just a month after our visit, an evacuation order was issued for Jasper due to devastating wildfires in the area. All residents and visitors were evacuated and approximately 30% of the townsite was burned to the ground during the blaze.

Jasper to Edson

Back on board The Canadian, we were originally set for a three hour journey to Edson, where we planned to alight. However, our anticipated arrival time of around 3:30 PM was delayed to approximately 8:30 PM due to a series of delays. The Canadian stopped on multiple occasions to allow freight trains to pass, often for over an hour at a time.

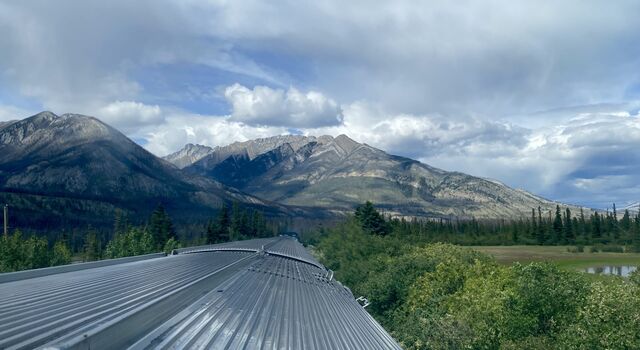

Even the extensive delays, however, could not take away from the breathtaking scenery along this segment of the route. Indeed, the stretch of track between Jasper and Hinton was the highlight of our journey on The Canadian. I had heard that this section of the route was particularly scenic, and this was one of the reasons we had decided to continue our journey on the train east of Jasper.

The train ran alongside the Athabasca River, the longest river in Alberta at 1,538 kilometres, which is renowned for its stunning turquoise waters. Soon after, we were treated to magnificent views of Roche Miette, towering at 2,316 metres within Jasper National Park. My guidebook informed me to keep an eye out for elk along this stretch of the Athabasca Valley. Mountains surrounded us on both sides of the track—the Bosche Range on one side and the Miette Range on the other.

There were again excellent views as The Canadian travelled around a large bend near the hamlet of Brûlé.

After many hours of delays, we pulled into the town of Hinton, where the Rocky Mountains finally faded from view. Hinton is the sight of an 1886 train collision between a Canadian National Railway freight train and a VIA Rail passenger train, which sadly killed 23 people and was the deadliest rail disaster in Canada.

When we finally alighted in Edson, a small lumber town dubbed ‘the gateway to the last great west’, we found it to be a quiet place with almost nothing to offer. We did, however, relish the novelty of exploring a Walmart. For dinner, my travel companion decided to order another Canadian delicacy: poutine. It was not a favourite of ours. For anyone curious about why we decided to alight in Edson, this was because we had arranged to meet our friends (who would be our travel companions for the next two weeks) in Edson the following morning.

Jasper National Park and Surrounds

The following day we met our friends in Edson and travelled back to Jasper, this time by car. We spent three days exploring Jasper and its surrounds. We stayed at the Alpine Village Cabin Resort, situated directly across from the Athabasca River. We loved the charming and authentic log cabins and were sad to hear that half of these cabins were burned to the ground in the aforementioned wildfire that tore through Jasper National Park, mere weeks after our visit.

Our first day in Jasper was an adventure to remember as we hiked the Sulphur Skyline Trail. With an elevation gain of 685 metres, it wasn’t the toughest hike I’ve ever done, but the conditions certainly made it challenging, with heavy snow in the middle of summer! The final scramble to reach the summit had us navigating through knee-deep snow in some places. It was a very memorable experience and the best hike we did on our trip. Afterward, we unwound with a relaxing soak in the Miette Hot Springs.

We also enjoyed hiking the Maligne Canyon and Valley of the Five Lakes trail. The former is the deepest canyon in Jasper National Park, with a depth of more than 50 metres at certain points.

After our time in Jasper, we set off down the Icefields Parkway—a spectacular 227 kilometre stretch of mountain road leading to Lake Louise. Notable stops en route included Athabasca Falls, the Athabasca Glacier, and Peyto Lake. We enjoyed a three hour guided hike on the glacier, where we learnt about its formation and the role glaciers play in shaping the landscape. It is necessary to join a guided tour to reduce the risk of falling down a deep crevasse.

Our accommodation was located between Lake Louise and Banff, close to Morant’s Curve—a scenic viewpoint along the Bow River where trains pass around a bend through the Canadian Rockies. This iconic spot often featured in the Canadian Pacific Railway’s promotional materials. Indeed, while visiting Lake Louise, we were able to sneak into the famous Fairmont Château Lake Louise where I purchased a poster of The Canadian at this very location. We drove past Morant’s Curve on multiple occasions and were lucky enough to eventually see a train passing through.

The area surrounding our accommodation was particularly notable for the abundance of wildlife we encountered. In particular, on the stretch of road (the Bow Valley Parkway) between Lake Louise and our accommodation, we regularly came across black bears and grizzly bears, strolling right alongside the highway. We must have seen about 10 bears in total, much to the surprise of even the local residents. We even saw ‘The Boss’ (identifiable by his distinctive ears): a notorious grizzly bear who has fathered numerous cubs in Banff National Park. The Boss regularly eats black bears and has even survived being struck by a train! He is pictured in the bottom right image below.

Our visit to Moraine Lake was a highlight of the trip and is probably the most beautiful place I’ve ever been. Readers should be aware that private vehicles can no longer access Moraine Lake; visitors must instead purchase a shuttle ticket from Parks Canada. The round-trip shuttle fare is quite reasonable at around $8, but tickets need to be purchased about two months in advance. They also tend to sell out almost immediately. We managed to secure tickets by having three of us log on simultaneously the moment they were released. While I noticed one or two companies offering same-day shuttle services at the Lake Louise ‘Park and Ride’, their prices were about ten times higher and they also sold out very quickly.

Lake Louise was also very beautiful, but it was extremely busy and wasn’t quite as impressive to me as Moraine Lake.

Our time in the resort town of Banff was another highlight. While it’s certainly a busy tourist destination, I found myself enjoying Banff even more than Jasper. The town of Banff was established in the 1880s, following the construction of the transcontinental railway through the Bow Valley.

One activity we enjoyed in Banff was via ferrata (which translates to ‘iron path’). Via ferrata is a protected climbing route equipped with steel fixtures such as cables, ladders, and suspension bridges, which climbers can clip their harness into. We did a four hour guided route on the cliffs above Mt Norquay, just outside downtown Banff.

After our time in Banff and Lake Louise, we continued on to the hamlet of Bragg Creek and the city of Calgary. However, as these destinations are less closely related to the railway, I shall end this post here. The Canadian has always been on my bucket list of train journeys and I’m glad I was able to experience the most beautiful segment of the route through the Rocky Mountains. Now that I’ve completed this leg of the journey, I don’t feel a strong compulsion to complete the remaining segment across the prairies and the rest of Canada, although it would certainly be nice to spend four nights on the train and have the experience of eating every meal in the dining carriage, which is included for sleeper car passengers. If I ever complete the full route, I will have to do so in the middle of winter so I can experience the snowy landscape.

Robin Neillands, ‘Across Canada from the Great Lakes to the Pacific Coast’, in Train Journeys of the World (The Automobile Association, 1993) 118, 118. ↩︎

Melissa Graham, Trans-Canada Rail Guide: Rail Routes, Maps, City Guides (Trailblazer Publications, 6th ed, 2019) 68. ↩︎

Ibid. ↩︎

Ibid 69. ↩︎

Julian Holland, Great Railways of the World (Collins, 2016) 262. ↩︎

Graham (n 2) 71. ↩︎

Ibid 70. ↩︎

Ibid 71. ↩︎

Patrick Poivre d’Arvor, First Class: Legendary Train Journeys Around the World (Vendome Press, 2007) 91. ↩︎

Time Out, Great Train Journeys of the World (Time Out, 2009) 42. ↩︎

Ibid. ↩︎

Ibid. ↩︎

Graham (n 2) 74. ↩︎

Poivre d’Arvor (n 9) 92. ↩︎

Graham (n 2) 77. ↩︎

Poivre d’Arvor (n 9) 92. ↩︎

Timothy Wheaton, The Great Trains: Luxury Rail Journeys of the World (Bison Books, 1990) 94. ↩︎

Poivre d’Arvor (n 9) 92. ↩︎

Graham (n 2) 78. ↩︎

Graham (n 2) 79; Holland (n 5) 262. ↩︎

Graham (n 2) 79. ↩︎

Max Wade-Matthews, The World’s Great Railway Journeys (Hermes House, 1999) 11. ↩︎

Holland (n 5) 262. ↩︎

Wheaton (n 17) 93. ↩︎

Holland (n 5) 262. ↩︎

Neillands (n 1) 119. ↩︎

Anthony Lambert, The 50 Greatest Train Journeys of the World (Icon, 2016) 202. ↩︎

For a fantastic view of the city with the peaks of the North Shore Mountains behind it, take a walk up Cambie Street. ↩︎

Holland (n 5) 267. ↩︎

Annie Bergeron-Oliver, ‘Back on track: NDP bill aims to make train passengers a priority’ (CTV National News, 6 January 2024, online). ↩︎

Ibid. ↩︎

Mission Museum, Billy Minor (online). ↩︎