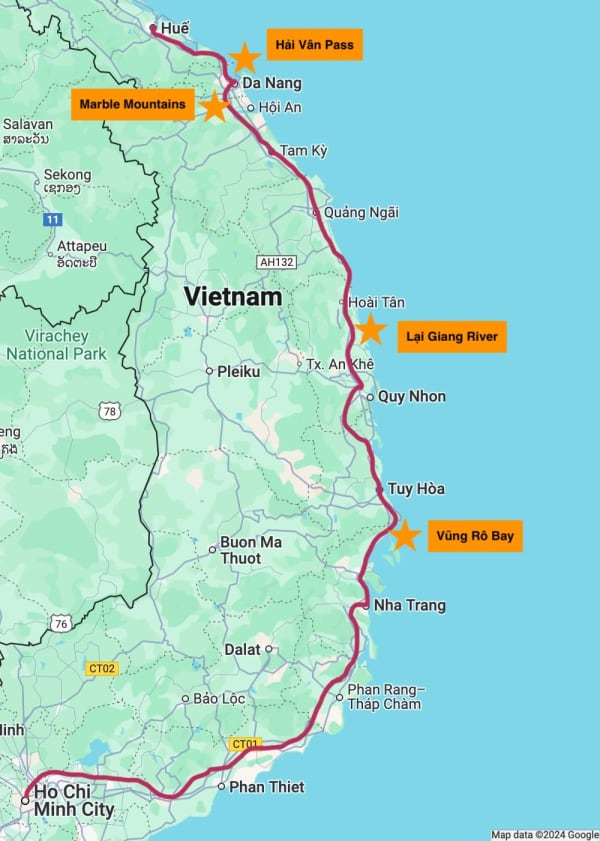

In July 2024 I rode the Reunification Express (the North–South Railway) between Ho Chi Minh City and Huế in Vietnam. We passed some incredible scenery en route, including as the train wound its way over the iconic Hải Vân Pass.

The railway links Saigon (now officially Ho Chi Minh City) in the south of Vietnam to Hanoi in the north. Trains that run on this line are dubbed the ‘Reunification Express’,1 with approximately five passenger trains per day travelling in each direction, taking about 34 hours to travel the full 1,726km between Ho Chi Minh City and Hanoi. My journey was on the southern half of the route, from Ho Chi Minh City to the ancient city of Huế.

Our journey took us through a diverse array of landscapes, from Vietnam’s scenic coastline along the South China Sea, to dense jungles, sprawling rice fields, and bustling cities. Along the way, we glimpsed the daily lives of many Vietnamese people, passing through tiny fishing villages and rural settlements where locals, wearing their conical hats, cycled along narrow paths or toiled in the fields, maintaining a rhythm of life that has remained unchanged for generations.

While the Vietnam Railway website notes that this train is no Orient Express,2 it undoubtedly has its own distinct charm. In 2024, Lonely Planet named the Reunification Express ‘one of Southeast Asia’s best-loved railways – and one of the most epic overnight train journeys in the world.’3

The purpose of my trip to Vietnam was to lead a study tour for 20 law students, immersing them in the complexities of Vietnam’s legal system. Naturally, I also took the opportunity to incorporate an overnight train journey into the weekend curriculum!

We left Melbourne on a cold winter morning and journeyed to a hot and humid Vietnam. As we flew, I was mesmerised by the enormous span of the Sultan Haji Omar Ali Saifuddien Bridge in Brunei. It is the longest bridge in Southeast Asia with a length of 30 kilometres.

History of Vietnam’s North–South Railway

The first miles of track on Vietnam’s North–South Railway (at the time ‘the Transindochinois’) were laid by French colonists in 1899. The Railway was primarily constructed for commercial purposes, facilitating the transport of goods including rubber, coal, rice, tea, and coffee.4 Completed in 1936, the Railway’s early travel times between Saigon and Hanoi were surprisingly similar to the journey durations of today’s modern trains! For passenger travel, the train largely catered to European expatriates residing in the Vietnamese countryside. The early trains were opulent, featuring plush sleeping cars, a restaurant, a movie theatre, and even a hairdresser! However, this era of prosperity was short-lived.5 As the 20th Century progressed, the Railway became deeply intertwined with Vietnam’s turbulent history.

With the outbreak of World War II, French Indochina (which comprised Vietnam, Laos, and Cambodia) was invaded by Japan. The Japanese forces relied heavily on the Vietnamese railway system, making the North–South Railway a prime target for sabotage by the Viet Minh resistance (a national coalition initially formed to seek independence for Vietnam from the French Empire). Additionally, the Railway became a target of American airstrikes, with the United States providing covert support to the Viet Minh in their fight against the Japanese in French Indochina. Unsurprisingly, the Railway was heavily damaged. Following the withdrawal of the Japanese at the end of the war, efforts were launched to repair the seriously damaged North–South line.6

However, in the aftermath of World War II, the First Indochina War (1946–1954) erupted, and the Railway was again the object of Viet Minh sabotage, this time directed at the French. Viet Minh guerrillas fighting for independence attacked armoured trains that travelled the line.7 When France withdrew from Vietnam in 1954, following the signing of the Geneva Conference agreement, Vietnam was divided in two: North Vietnam was controlled by a Communist government, and South Vietnam by a US-supported regime. The railroad was similarly split in two at the Hiền Lương Bridge.

During the Vietnam War (1955–1975), both the North and South lines were again heavily damaged. American bombings disabled the tracks in the North and sabotage by the Viet Cong (the Communist-led guerrilla force that fought against South Vietnam and the United States) destroyed tracks, tunnels, and bridges in the South.8

In 1975, the newly unified Vietnam Communist government reconnected the two halves of the badly damaged line. Many of the Railway’s 1,334 bridges and 27 tunnels had been completely destroyed and had to be rebuilt, despite scant technology and limited materials.9 Restoring the line ‘was a sign of the country’s unity and a symbol of victory following twenty years of war’.10 The Railway has since served as ‘a symbol of national healing and solidarity’.11

Our journey on the Reunification Express started in Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam’s most populous metropolis.

Ho Chi Minh City

The French colonial period left a lasting imprint on Ho Chi Minh City’s architecture, evident in several stately buildings that evoke the grandeur of 19th-century France. The Saigon Central Post Office is one of the finest examples, designed by the French architect Gustave Eiffel. Built between 1898 and 1909, the City Hall is another of Ho Chi Minh City’s emblematic French buildings, directly evoking its Parisian counterpart. In 1975, with the reunification of Vietnam, the building became the headquarters of the People’s Committee.

My favourite building was the pink Tân Định Church, notable for its flamboyant Neo-Romanesque architecture. Other notable buildings and views in Ho Chi Minh City are pictured below.

Tân Định Church, constructed 1876

Independence Palace

Landmark 81 (tallest building in Vietnam)

Thiên Hậu Temple

District 5, Ho Chi Minh City

Tôn Đức Thắng Boulevard

The Cafe Apartments

Book Street

View of the Saigon River from Thảo Điền

Huyện Sỹ Church, constructed 1902

Saigon Opera House, constructed 1898–1900 for French troops stationed in Saigon

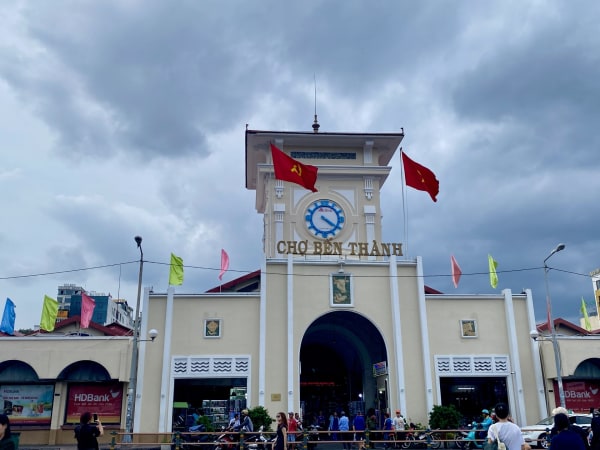

Bến Thành Market

My least favourite part of Ho Chi Minh City was the absolutely chaotic traffic. Millions of motorbikes weave through the streets (and, annoyingly, even onto the sidewalks), honking their horns at every turn. Crossing the road, or even just trying to walk on the sidewalk, feels like a game of survival. When trying to cross the road, there’s no choice but to step out with confidence, manoeuvring your way across and praying the motorbikes will stop. It’s such a headache that even something as simple as going outside to grab a quick bite for lunch can feel like a hassle. On the plus side, Ho Chi Minh City’s first metro line officially opened in December 2024, after over a decade of delays. The project, funded largely by Japanese government loans, finally provides a metro (even if just one line at this stage) for the city’s population of nearly 10 million people.12 While it is unfortunate the metro was not yet in operation when I visited in July 2024, it is sure to make at least some difference in what is an incredibly unwalkable city. Interestingly, the Vietnam International Arbitration Centre is reportedly hearing a US $152 million claim by the Japanese contractor who built the metro line against Vietnam’s government-owned railway company over the severely delayed project.13

We sampled a diverse array of foods in Vietnam and each was definitely a unique experience. The food was also very affordable. For example, my mystery lunch in Đà Nẵng (bottom centre image below) was practically inedible, but on the plus side, it only cost 20,000 VND (just over $1 AUD).

Bánh mì

Fish lunch in the Mekong Delta region

Rambutan on the Cần Thơ River

Sugarcane juice in Hội An

Lunch in Thảo Điền

Bánh Xèo in Huế

Coconut on the Mekong River

Half hatched duck egg with baby duck inside

Coconut snack, Cái Răng Floating Market

Mystery lunch in Đà Nẵng.

Mystery dish in the Mekong Delta region

Saigon Station

Our journey on the Reunification Express began at what my guidebook describes as Ho Chi Minh City’s ‘rather humble-looking station’, which still bears the old name Sai Gon.14 Despite its modest exterior, this is the busiest train station in Vietnam. The station is relatively new, having been built in 1983.

Our trip to Saigon Station was not without incident. Neither our tickets nor booking confirmation included an address for the station, and it was strangely difficult to find the correct details online. We had no choice but to rely on the address provided by Google Maps. Unable to communicate with the taxi driver, a group of us were dropped off in a back alley on the other side of the tracks. It seemed the driver knew full well where we were actually headed as he soon claimed he would take us to the train station if we paid him extra. Not trusting him, we opted to try and walk around the block instead. Navigating Ho Chi Minh City’s congested streets and sidewalks in the dark was a challenging task, and I began to seriously worry that we might miss our train altogether. Despite having left our hotel a full hour before the train’s departure (and the hotel being just 10 minutes away from the station), we found ourselves hopelessly lost. I was carrying all 22 train tickets for our group—20 students, myself, and the other tour leader—and the minutes were slipping away. Thankfully, we reached the station with a mere 10 minutes to spare and were relieved to see that the other students had already arrived.

On Board the Train

For our journey between Ho Chi Minh City and Đà Nẵng, we were booked into the six-berth air-conditioned sleeper compartments, departing Saigon Station at 8:35PM and scheduled to arrive in Đà Nẵng at 1:40PM the following day. However, the expected 17-hour journey ended up taking approximately 18.5 hours.

Trains on the North-South Railway travel at a maximum speed of just 50km/h.15 Our train was SE2, one of the better trains, its carriages having been refurbished in the last ten years. The cost of a ticket was approximately $65 AUD per person.

There are two classes of seating: “hard” and “soft”. In the seating carriages, “hard” seats consist simply of wooden benches, while “soft” seats are, as the name suggests, much more comfortable. In the sleeping carriages, the difference lies in the number of berths per compartment. “Hard” sleepers feature six berths, whereas “soft” sleepers accommodate four.

According to my guidebook, train attendants generally frown upon passengers purchasing an entire compartment for privacy and may assign other passengers to any unoccupied bunks.16 There is also a ‘VIP berth’ on the SE2 train which has only two beds in the compartment.

Before the trip, I had read that bed sheets on the Reunification Express are not changed between passengers, meaning only the sheets at the start of each journey (either from Ho Chi Minh City or Hanoi) are fresh. In other words, if someone were to alight at an intermediate stop in the middle of the night and another passenger boarded, the new passenger would have to settle into a used bed. On our journey, however, I did observe the train attendant changing the sheets on at least one bed after a passenger vacated their berth a few hours into the journey.

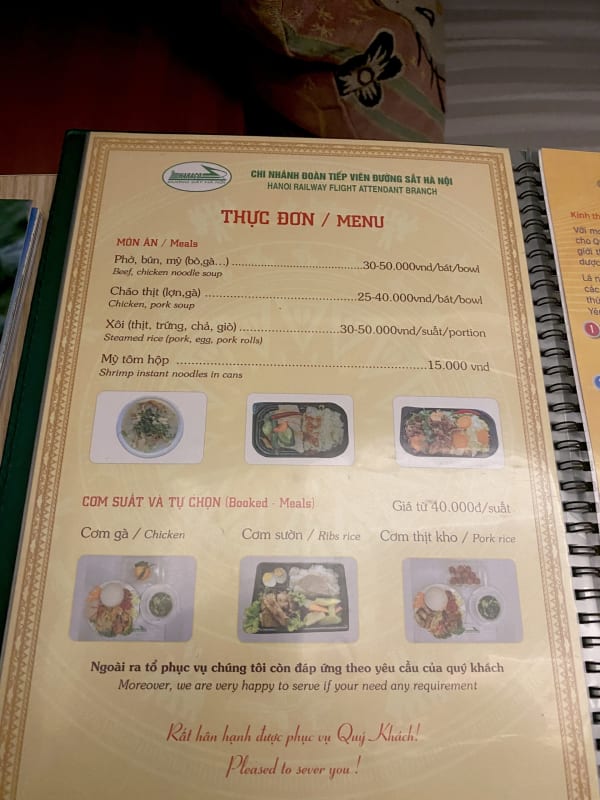

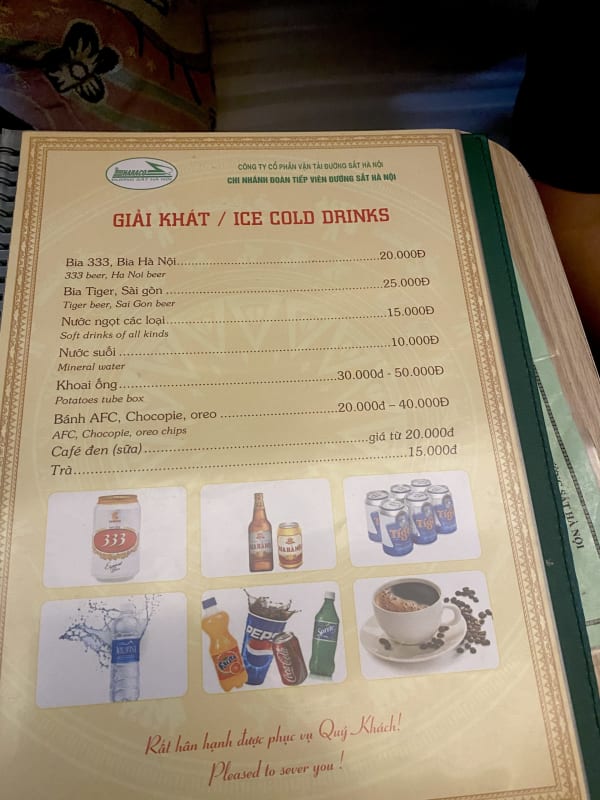

Throughout the ride, train attendants periodically circulate to sell drinks and snacks. The train also makes occasional stops long enough for passengers to quickly purchase additional snacks from vendors at the stations.

Ho Chi Minh City to Đà Nẵng

As the train left Saigon Station, the towering skyscrapers and glowing lights of the city gradually faded into the distance. Darkness had already settled in, and a lively communal atmosphere took hold on board the train. Everyone stayed up into the early hours of the morning, playing cards and chatting happily in the cabins.

We slept through the train’s stop in Nha Trang, approximately 400km into the journey. According to my guidebook, this is Vietnam’s most famous seaside resort.17 I awoke early in the morning, around 5:15 AM, just as the train began to skirt the edge of Vũng Rô Bay, a picturesque bay in Phú Yên Province, nestled at the edge of the Cả Pass mountains. I quickly got up and made my way to the vestibule, where I spent the next four hours taking in the view from the open windows on both sides of the train. For me, this was the highlight of the journey. Sadly, the students slept through it all. As the train snaked along the coastline, passed sprawling rice fields, and travelled alongside tiny villages, I became immersed in the rhythm of daily life in Vietnam—locals tending to the fields, their work unfolding in harmony with the land.

Aside from the stunning scenery, I observed some curious quirks of train travel in Vietnam during my morning in the vestibule. Our carriage attendant had a habit of locking the door between carriages at seemingly random intervals. I assumed this was to ensure that passengers boarding at upcoming stations stayed in their designated carriages and could not wander off in search of better seats. However, the doors would remain locked for a very long time after each stop, creating a peculiar predicament for anyone who had previously stepped out of their carriage, whether to visit the dining car, or search for an available restroom. In such cases, you could easily find yourself stranded outside your carriage, separated from your belongings for well over an hour. One middle-aged man from my carriage, having ventured off to the dining car, spent a long time futilely banging on our carriage door, pleading with me to let him back in, despite the fact I was neither the carriage attendant nor in any position to unlock the door.

Another vestibule incident unfolded early in the morning when a different middle-aged Vietnamese man ambled in, picked up a broom, and randomly began poking at the ceiling of the carriage. It was a very odd and almost comical moment. Much to his astonishment, a torrent of water soon began to pour down from the ceiling, all over the floor of the train. He stumbled back, wide-eyed with disbelief. The carriage attendant rushed in, her expression a mix of alarm and annoyance. They exchanged rapid-fire words in Vietnamese and the man, feigning innocence, shrugged and raised his hands in an exaggerated gesture of confusion, as if to say, “what could I possibly have done?”

Highlights during the second half of our journey included views of the Lại Giang River and An Khê Lagoon. A few hours before our arrival in Đà Nẵng, we passed the city of Tam Kỳ which is apparently famous for its chicken rice and many pristine beaches.

Mỹ Trinh

Mỹ Trinh

Crossing the Lại Giang River on the Bồng Sơn Railway Bridge

Passing the An Khê Lagoon

Thuỷ Thạch Station

Đức Phổ District

Đức Phổ District

Graves scattered across the land in the Đức Phổ District

River Vệ

Tam Hiệp, Núi Thành and the entry to the North Chu Lai Industrial Park

Tam Kỳ Station

Thánh xá Liêm Lạc (religious institution)

After 18.5 hours, we alighted in the city of Đà Nẵng which lies on the coast of the South China Sea and is one of Vietnam’s most important port cities.

Đà Nẵng

I was delighted to see a sign on the outside of Đà Nẵng’s railway station which declares the Reunification Express to be the ‘world’s most incredible and worth-experiencing train’! In front of the station, there is also an interesting vintage steam locomotive.

From Đà Nẵng, we made the short trip to the lantern-lined alleyways and covered bridges of Hội An. On the way, we stopped to visit the Marble Mountains, a group of five limestone peaks. The mountains each have cave entrances, with several Buddhist sanctuaries inside.

Hội An

Hội An is a UNESCO World Heritage Site that is steeped in history and rich in architectural diversity, from traditional wooden Chinese shophouses (Hoi An was originally a port for Chinese traders), to vibrant French colonial buildings.18 The city is famous for being a well-preserved example of a small-scale South-East Asian trading port that was active from the 15th to 19th centuries.19

Our accomodation was the Coco River Resort & Spa, located on the Thu Bồn River. This was a beautiful property, although it was unexpectedly hard to arrange transportation to the centre of Hội An from this location.

Travelling by train over the Hải Vân Pass between Đà Nẵng and Huế

The following day, I resumed my journey along what I had read was the most scenic stretch of the railway between Đà Nẵng and the imperial city of Huế. For some reason, the students felt that 18.5 hours on the train was enough. While some were interested in visiting Huế, none elected to take another train ride over their free weekend in the region.

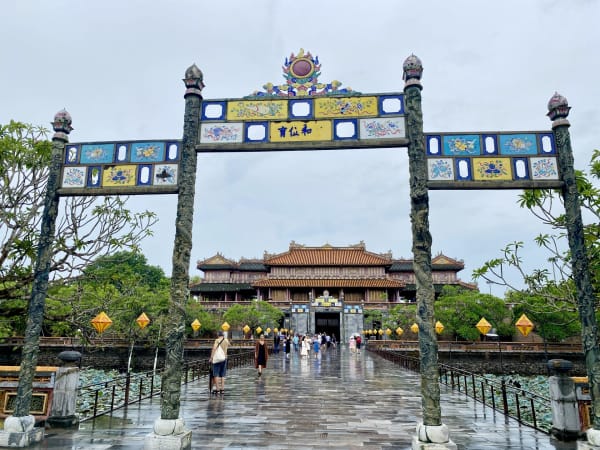

Due to the train schedule, I first travelled to Huế by coach, before boarding a train travelling from Huế back to Đà Nẵng. Huế was the imperial capital of Vietnam during the Nguyễn dynasty from 1802 to 1945. The seat of the Nguyễn emperors was the Imperial City: a walled enclosure within the citadel which contains the intricate palaces that housed the imperial family, as well as various shrines and sprawling courtyards and gardens.

After an enjoyable few hours in Huế, I made my way to the railway station which was constructed by French colonists in the early 1900s.

The journey between Huế and Đà Nẵng lasted just over 3.5 hours. The ticket for this iconic route, which includes one of the world’s most scenic stretches of track along the Hải Vân Pass (a 21km lush green mountain pass), cost just 210,000 VNĐ (approximately $13 AUD). I was on the HĐ3 train, which is a special tourist train, introduced in 2024, which travels exclusively over this picturesque section of the North-South Railway between Huế and Đà Nẵng.

Although the tourist train follows the exact same route as the train I was on the previous day from Ho Chi Minh City, the key difference is that the HĐ3 is apparently supposed to make a 10 minute stop at the scenic Lăng Cô Station, allowing passengers to admire the stunning views over the famous Lăng Cô Bay. Whether this actually occurred, however, remains unclear. There was no announcement, and no one seemed to alight, but the train did pause for about 10 minutes, although not at Lăng Cô Station, but in what appeared to be the middle of the jungle (though it was somewhat close to the station). I have no idea whether or not this was the scenic stop.

For the best views while travelling in the direction of Huế to Đà Nẵng, it is preferable to sit on the left side of the train, so I made sure to secure seats accordingly. As the train wound its way through the Hải Vân Pass, I was treated to excellent views of the South China Sea. The train meandered through tunnels and over bridges, winding past sheer cliffs and dense jungles, with glimpses of sandy beaches and distant islands. Beyond its natural beauty, the Hải Vân Pass is also infamous for its treacherous terrain. The Vietnamese poet Nguyễn Phúc Chu (1675–1725) famously referred to it as “the most dangerous mountain in Vietnam.”20

The railway over the Hải Vân Pass has a dramatic history. In June 1953, over 100 people lost their lives when two locomotives and 18 carriages of a passenger train plunged 50 feet after a sabotaged viaduct collapsed beneath them. Officials reported that a powerful explosive charge detonated just as the train reached the viaduct.21 This occurred during the period when the region was frequently targeted by the Viet Minh in their campaign against French colonial rule. The Hải Vân Pass again saw tragedy in 2005 when a passenger train on the North–South Railway derailed just north of the Pass, killing 13 people and injuring hundreds more. Investigations revealed that the train was travelling 20 km/h over the speed limit when the accident occurred. Due to the location’s inaccessibility by road, rescuers had to rely on boats to reach the crash site.22

Thankfully, my journey over the Hải Vân Pass was without incident. While the weather was not ideal, the scenery was still impressive. On a sunny day, I imagine the views would be breathtaking.

Just one month prior to my journey on the Reunification Express, I was riding The Canadian through the majestic Rocky Mountains. The scenery along Vietnam’s North-South Railway was not quite as dramatic as travelling through Canada’s snow-capped peaks and turquoise lakes. However, Vietnam’s Reunification Express proved to be, in its own right, an even more exciting journey. As the train wound its way through Vietnam’s rural heartland, I felt as though I was glimpsing a side of the country that few outsiders get to see, a world so different from anything I was familiar with. The hours I spent in the vestibule in the quiet hours of the early morning, running from side to side to capture the lush countryside, rural villages, and the ever-changing landscape unfolding outside the train’s window, will always be a special memory.

See ‘History of Vietnam’s North–South Railway’ below. ↩︎

Vietnam Railways System, ‘Reunification Express Train’ (online, 2025). ↩︎

Lonely Planet, ‘24 of the world’s most incredible train journeys’ (online, 2 January 2024). ↩︎

Time Out, Great Train Journeys of the World (Time Out, 2009) 134. ↩︎

Lonely Planet, Amazing Train Journeys (Lonely Planet, 2018) 129; Emma Thomson, ‘A journey through history on board Vietnam’s Reunification Express train’ (National Geographic, online, 2019). ↩︎

Lonely Planet (n 5) 129; Time Out (n 4) 134. ↩︎

Ibid. ↩︎

Ibid. ↩︎

Sarah Baxter, A History of the World in 500 Railway Journeys (Aurum Press, 2017) 339. ↩︎

Franco Tanel, Travel By Train (White Star, 2023) 193. ↩︎

Lonely Planet (n 5) 130. ↩︎

See International Railway Journal, ‘Ho Chi Minh City finally opens first metro line’ (online, 27 December 2024). ↩︎

Vietnam Investment Review, ‘Hitachi requests additional $157 million for Metro Line No.1’ (online, 4 June 2024). ↩︎

Lonely Planet (n 5) 130. ↩︎

Franco (n 10) 194. ↩︎

Time Out (n 4) 139. ↩︎

Franco (n 10) 195. ↩︎

Ibid 194. ↩︎

UNESCO World Heritage Convention, Hoi An Ancient Town (online, 2025). ↩︎

Ban Tu Thu, ‘Names of Vietnam’ (The Holy Land of Vietnam Studies, online, 2020). ↩︎

Vietnam Trains, ‘Train travel over the Hai Van Pass’ (online, 2025). ↩︎

ABC News, ‘Train derails in Vietnam, 13 killed’ (online, 13 March 2005). ↩︎