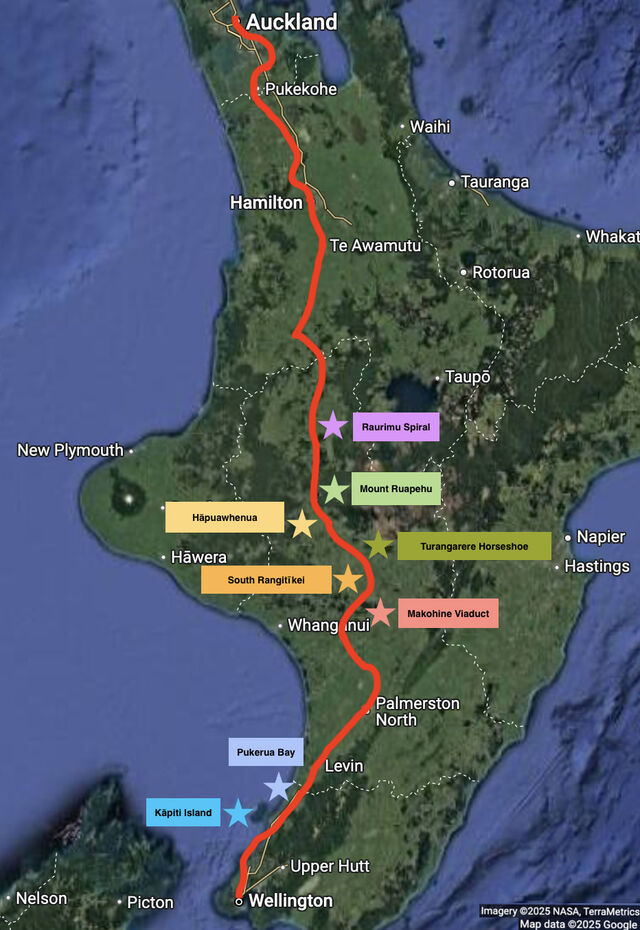

The Northern Explorer travels 681 kilometres, from New Zealand’s capital city of Wellington, up almost the entire length of the country’s North Island to its largest city of Auckland. En route, the train winds through vast farmlands and alongside dramatic river valleys and rugged coastline. The highlight of the journey, however, unfolds as the train soars over several towering viaducts as it approaches the volcanic heart of New Zealand’s North Island. I had the pleasure of experiencing this 11 hour scenic train journey in December 2024.

History of the Route

Completed in 1908, the Northern Explorer traces the path of New Zealand’s historic North Island Main Trunk Railway. Prior to the railway’s completion, travelling between Auckland and Wellington was a gruelling undertaking, whether by sea or overland via horse and carriage. Constructing the railway was no small feat. The project faced considerable challenges, including treacherous terrain and complex territorial negotiations. Parts of the proposed route passed through Māori land, necessitating careful negotiations with local tribes.1 It took nearly three decades to complete the railway. Upon its opening, the first steam trains took around 20 hours to travel from end to end.2 Today, the Northern Explorer covers the same route in just over half that time, departing from both Auckland and Wellington three times per week. My journey on the Northern Explorer began in the charming city of Wellington.

Wellington

Situated near the North Island’s southernmost point, Wellington is known for being the world’s windiest city. I enjoyed my time strolling around and admiring the city’s many Art Deco buildings.

Beehive (New Zealand's Parliament)

Parliament Library, constructed 1899

Whairepo Lagoon

St Mary of the Angels, constructed 1922

Cuba Street

St John's Church, constructed 1885

Bank of New Zealand Building, constructed 1901

Old Government Building, constructed 1876 (now home to the Victoria University of Wellington Faculty of Law)

Dominion Farmers Institute Building, constructed 1920

Public Trust Building, constructed 1909

The Opera House, constructed 1914

Oriental Bay Beach

Houses on Oriental Parade

Oriental Bay

A highlight from my time in Wellington was the hike up to Mount Victoria Lookout which provides great views over the city and Wellington Harbour.

However, my favourite attraction was undoubtedly the Wellington Cable Car. This funicular railway connects Lambton Quay (Wellington’s main shopping street) to the suburb of Kelburn, perched on a hill high above the city centre. Interestingly, Wellington is not just home to this iconic cable car—over 150 private cable cars also navigate the city’s steep inclines, transporting locals to their hillside residences.

The Cable Car

At the close of the 19th Century, Wellington was New Zealand’s fastest-growing city, and its expanding workforce desperately needed housing. The hills rising directly above the city centre offered the perfect solution, but a transport link was needed. In 1902, the Wellington Cable Car opened, offering an easy means of access between the city and suburban hills. The winding gear of the cable car was powered by steam until 1933 when it was replaced with electricity.

Unfortunately, in the days before modern work health and safety practices, numerous accidents occurred. One tragic incident involved an 80-year-old man whose legs were caught between the cable car and the platform. Another elderly man was thrown from the cable car when it rolled back down the incline due to insufficient braking, resulting in serious head and facial injuries. A 10-year-old girl also suffered a severe injury when her foot was amputated by the wheels of the cable car after she stepped off too soon. However, it wasn’t until a worker sustained a serious injury in 1973 that a thorough safety review was finally initiated, ultimately leading to the temporary closure of the line.3

A new fully automated system was finally introduced in 1979 and two new cable cars designed and constructed in Thun, Switzerland were installed. The track was upgraded and numerous safety features were added, including earthquake protection. Despite these modern improvements, the new cars retained elements of their predecessors’ charm, including their signature red exteriors and interiors adorned with varnished hardwood.

Today, a trip on the cable car takes around five minutes, and passengers are treated to the spectacle of 45,000 LED lights illuminating two tunnels along the way. At the top, visitors are greeted by a stunning viewpoint offering a panoramic view over Wellington and its harbour, as well as access to the Wellington Botanic Garden and the Cable Car Museum. The museum houses one of the historic red rattler cable cars that operated during the 1950s–1970s, along with a winding machine room that was fully operational from 1930–1978, where visitors can see the machinery once used to haul the cable cars up the hill. The museum also contains interesting information about Lorrayne Ruka-Issac, the cable car’s first female driver, who also operated cable cars in the UK, Hong Kong, San Francisco, and Switzerland.

Wellington Railway Station

I was shocked when I arrived at Wellington Railway Station, having not expected to be greeted by such a grand structure.

After checking in for my journey inside the station, I made my way to the platform. All large bags and backpacks are required to be stored in the train’s luggage carriage, so it is advisable for passengers to ensure they also bring a smaller bag for the journey.

On Board the Train

I found the staff on board the Northern Explorer to be exceptionally friendly. I was also pleased to find large windows which provided great views of the ever-changing scenery. Onboard commentary, provided through personal headsets, is also provided. The commentary covers details about the route’s history and upcoming sights. At the rear of the train is an open-air observation carriage, which is definitely the place to be during the most scenic parts of the journey. However, the open-air carriage was incredibly windy, so I would recommend bringing a wind jacket, as well as securing your phone or camera with a tie to avoid losing them in the gusts.

Unfortunately, passengers are unable to choose their seats for this journey (at least not online—it may be possible to do so if you live in New Zealand and can ring the company). I was fortunate enough to be assigned the perfect seat: a window seat on the right-hand side of the train, facing east. I had read that this was the slightly more scenic side when travelling from Wellington. In addition, I was seated in the carriage closet to the open-air observation deck. This allowed me to jump up from my seat and quickly proceed to the open-air carriage whenever we were passing particularly good scenery. However, even if your seat allocation is not ideal, the headset commentary provides information about upcoming views, giving passengers enough time to step out onto the observation deck. Alternatively, relocating to the café car would also allow you to switch to a window seat, or a seat on the other side of the train.

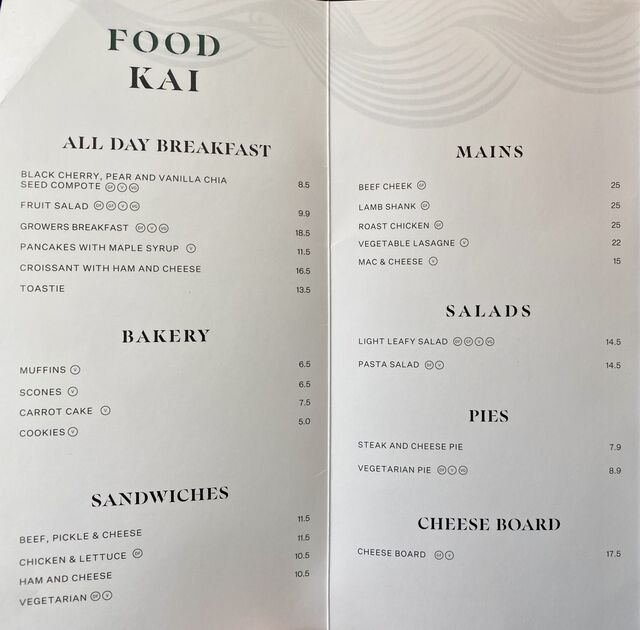

There is also a café car which serves a variety of drinks, hot meals, and lighter snacks.

I was seated behind a couple from Saskatchewan, Canada, who struck up a conversation with the couple from Victoria, Canada, seated across the aisle. The idle chatter continued throughout much of the journey. At one point, Mr Saskatchewan pulled out a pair of clippers and began trimming his fingernails. Each snip sent shards of nail flying across the carriage, as if the confined space were his own personal salon. If this disrespectful display wasn’t enough, he then moved on to flossing his teeth, all from the comfort of his seat. Oddly enough, no one seemed to mind his disgusting behaviour.

The Journey

The Northern Explorer set off from Wellington’s historic railway station just before 8 AM and pulled into Auckland’s Strand Station 11 hours later at 7 PM.

As the train departed New Zealand’s capital, passengers were treated to great views of Porirua Harbour. Between Pukerua Bay and Paekākāriki, the railway hugged cliffs high above the sea, offering great views of Kāpiti Island. Once the site of a thriving whale oil industry, the island is now a sanctuary for native New Zealand birds and plays a critical role in their preservation.4 Kāpiti Island is also known for its famous ice cream, which was served on board the train. Shortly after lunch, one lady in our carriage bought a Kāpiti ice cream from the café car, and soon after nearly everyone else in my carriage had followed suit!

Beyond Paraparaumu Station, the train veered along the edge of the Rangitikei River, where the water has carved the sandstone to create a narrow gorge with dramatic white cliffs.

For the next part of the journey, the train mostly travelled alongside rolling green hills. Along the way, I spotted many different variety of cows grazing peacefully, but surprisingly, there were almost no sheep in sight.

As the Northern Explorer followed the gorges of the Rangitikei Valley, it negotiated the river and its tributaries via five towering viaducts over a span of approximately 15 minutes. Just before reaching the first viaduct, the conductor made an announcement, giving passengers the opportunity to head to the observation deck. It became quite crowded at this point, so I recommend you do what I did and save the location of the first viaduct on your phone before departure. You can then follow along with the GPS, allowing you to secure a prime spot on the observation deck before the rush of other passengers.

The first viaduct, the Makohine Viaduct, was built in 1902 and stretches 229 metres across the valley.5 Next was the South Rangitīkei Viaduct, at 78 metres tall and 315 metres long, which holds the distinction of being the first in the world to use special energy-absorbing dampers in the foundations of its piers. In the event of an earthquake, the piers are designed to shift from side to side without collapsing.6

After crossing the Kaiwhatau River Viaduct, the North Rangitīkei Viaduct, and finally, the Toi Toi Viaduct, we ticked off another early highlight as the train travelled around the giant Turangarere Horseshoe Curve. The Northern Explorer then continued on to Waiouru Station, which, perched at 814 metres above sea level, is the highest train station in New Zealand.7

Crossing the Makohine Railway Viaduct

View from the Makohine Railway Viaduct which crosses the Makohine Stream Valley

The Northern Explorer heading into a tunnel

Crossing the South Rangitīkei Viaduct

View from the South Rangitīkei Viaduct which crosses the Rangitīkei River

The Northern Explorer travelling around a curve in Lower Kawhātau

Kawhātau Viaduct which crosses the Kawhātau River

View of the Kawhātau River from the Kawhātau Viaduct

Crossing the Rangitīkei River once again

The Northern Explorer travelling around a curve near Turangarere

Turangarere Railway Loop (horseshoe curve)

From here, the train ascended onto the North Island’s Volcanic Plateau as it again followed the Rangitikei River. It wasn’t long until we enjoyed unobstructed views of the imposing snow-capped Mount Ruapehu. This is New Zealand’s largest active volcano and the highest peak on the North Island.

We then passed Tangiwai, the site of the tragic Tangiwai railway disaster. On Christmas Eve in 1953, a railway bridge crossing the Whangaehu River collapsed beneath an express passenger train travelling from Wellington to Auckland. The locomotive and first six carriages plunged into the river below, resulting in the loss of 151 lives. The disaster was caused by the catastrophic failure of a dam holding back the crater lake of Mount Ruapehu. This unleashed a massive mudflow into the Whangaehu River, destroying one of the bridge’s support piers, mere moments before the train reached the bridge. The Tangiwai disaster remains New Zealand’s deadliest rail accident.

As the Northern Explorer navigated its way around the foothills of Mount Ruapehu, skirting the edge of Tongariro National Park, we crossed another series of high viaducts. First was the Hāpuawhenua Viaduct which stands at 51 metres high and 414 metres long. This impressive curved viaduct provides a great photo opportunity from the outdoor observation deck. From the viaduct, there are also views of the Ohakune Old Coach Road, which was previously used to carry passengers and goods by rail. Next was the Manganui-o-te-Ao Viaduct, notable for being the last piece of the North Island Main Trunk Railway to be constructed, finally connecting Wellington to Auckland by train. We then crossed the tallest of the three viaducts: the Makatote Viaduct, which is also the second largest on the Northern Explorer’s route.8

Before long, we came upon the historic Raurimu Spiral, a remarkable feat of engineering designed in 1898 to navigate the 139 metre ascent to the North Island’s Volcanic Central Plateau. As the train wound its way through the tight curves of the spiral, we were treated to stunning views. This world-renowned railway marvel employs a masterful combination of curves, horseshoe bends, tunnels, and even a full loop, allowing it to cross the steep slope between the elevated plateau and the valleys and gorges of the Whanganui River below.9

We reached the Raurimu Spiral approximately halfway through our journey from Wellington to Auckland. Unfortunately, the second half of the Northern Explorer’s route lacked the excitement of the first. While the views were pleasant enough, they couldn’t quite match the towering viaducts, snow-capped volcanoes, and remarkable engineering feats we experienced earlier in the journey.

It was late in the afternoon when we pulled into Hamilton Railway Station. There was no sign of New Zealand’s fourth largest city from this small and unassuming stop on its outskirts. Afterwards, we crossed the Waikato Plains before heading into Auckland.

About one-third of New Zealand’s population resides in Auckland, a fact that became clear as the train skirted the city’s suburban outskirts for nearly an hour. When we finally pulled into Auckland’s Strand Station, my time on New Zealand’s longest train journey came to an end.

After alighting from the train, there was still one final train-related thrill to experience. I had booked my accommodation for the night at Auckland’s Grand Central Serviced Apartments, housed in the city’s former main railway station, which has drawn comparisons to New York City’s Grand Central Terminal. Constructed in 1930, the station was the heart of Auckland’s railway network until 2003. While the building boasts an impressive exterior and grand interior, I unfortunately cannot recommend this accommodation option. It seems the space is also used for long-term accommodation, and the overall vibe just felt a little unsettling.

The following morning, I enjoyed a quick walk around the city before making my way to the airport.

With its spacious open-air observation carriage and stunning scenery between Wellington and the North Island’s Volcanic Central Plateau, a journey on the Northern Explorer is certainly memorable. As a tourist railway, it’s unfortunate that the cost makes it impractical for regular travel. If I lived in New Zealand, and the price of the train journey between Auckland and Wellington was comparable to flying, I would definitely elect to travel via train, much like I do between Melbourne and Sydney when time allows. Nevertheless, even as a tourist train, it’s definitely worth experiencing a trip on New Zealand’s longest railway journey at least once.

Sarah Baxter, History of the World in 500 Railway Journeys (Quarto Publishing, 2017) 18. ↩︎

Franco Tanel, Travel By Train (White Star, 2023) 218. ↩︎

Jay Èvett, ‘Fact or Fallacy? Five Urban Legends from the Cable Car Debunked’ (Te Curio Cabinet, Online). ↩︎

David Bowden, Great Railway Journeys in Australia and New Zealand (John Beaufoy Publishing, 3rd ed, 2023) 130. ↩︎

Great Journeys of New Zealand, ‘Northern Explorer’ (Online). ↩︎

Jock Phillips, ‘Bridges and tunnels - Notable bridges’ (Te Ara – The Encyclopedia of New Zealand, Online). ↩︎

Bowden (n 4) 130. ↩︎

Great Journeys of New Zealand (n 5). ↩︎

Lonely Planet, Amazing Train Journeys (Lonely Planet, 2018) 293. ↩︎